In this report

Generative AI chatbots: overhyped but still underestimated

Generative AI chatbots: overhyped but still underestimated

Key takeaways: At age 2, the most successful newcomer in tech history has a lot of growing up to do

- Generative AI chatbots like ChatGPT are wildly successful, but most users aren’t deeply moved by them. The generative AI companies need to branch out from their narrow base of enthusiasts.

- There are signs that AI chatbots may drive a massive increase in productivity, but most employers are surprisingly passive about deploying them. They need to be proactive.

- ChatGPT is by far the most popular AI chatbot, but Anthropic Claude won our competitive AI triathlon because it's the most personable. Microsoft Copilot was the most polarizing. People judge AI conversations the same way they judge human conversations, so companies building AI products need to pay close attention to the tone and formatting of responses, not just usability.

Summary: AI chatbots are amazingly successful, but still have very far to go

AI chatbots (technically, generative AI large language models like ChatGPT) are probably the fastest-growing software product in history. It took about 20 years for email to become ubiquitous on computers and 5-7 years for web browsers to do the same. In just under 2 years, ChatGPT and its competitors have reached almost all knowledge workers in the developed English-speaking world.

Because the change has been so rapid, there are many unanswered questions about AI chatbot use in business: What are people doing with AI chatbots? What benefits do they get? How do they feel about them? Which chatbots appeal to the most people? And what does all of this mean for companies looking to create AI-based products, and to adopt AI in their businesses?

In the fall of 2024, UserTesting conducted a major study of AI chatbot adoption and usage in businesses worldwide, including an extensive survey and video interviews. The results show the state of the AI chatbot business today and give strong indications of future problems and opportunities. Here are the key findings:

What we learned

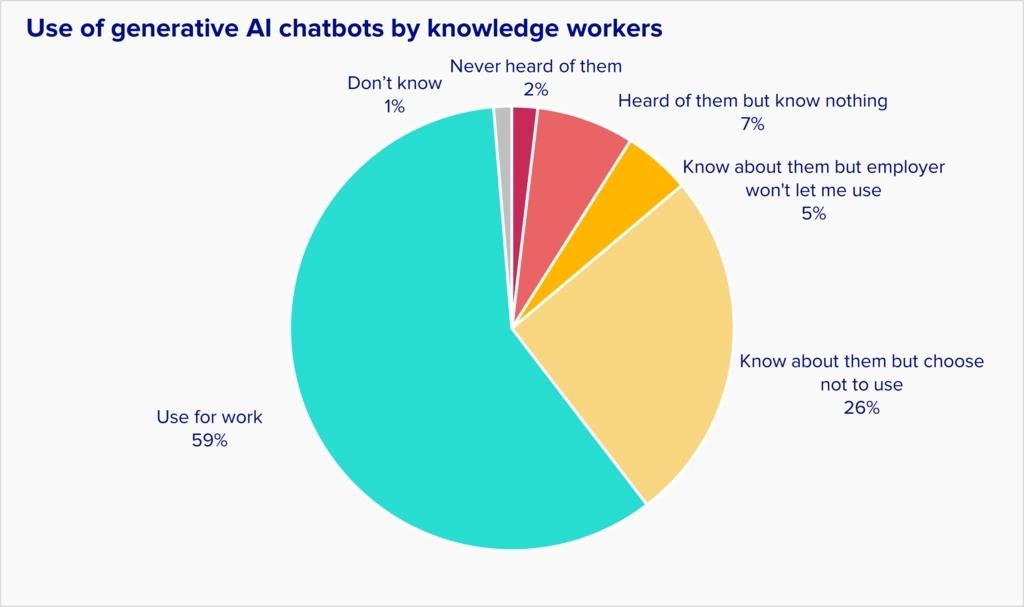

- AI chatbots have blasted past the early adopters. Almost two-thirds of knowledge workers in the developed, English-speaking countries are using AI chatbots, and most of the rest thought about it and decided they have no use for them. In the countries we studied, the market is close to saturated.

- The user reaction to AI chatbots is surprisingly inconsistent. Although most knowledge workers use AI chatbots for work, their usage patterns vary tremendously:

- About 20% of AI chatbot users are intensely passionate about them, use them heavily at work as a generalized personal assistant, and say they would be “very disappointed” if they could no longer use them. We call these users “Dedicated” because they are so committed to AI chatbots.

- Most other users would only be somewhat disappointed, or not disappointed at all, if they lost use of AI chatbots. We call the not-disappointed ones “Indifferent” users. They generally use AI chatbots as a tool for a few limited tasks, use it less frequently, and are much less excited.

The differences between these users are striking. Here are some video clips of them talking about AI, captured through the UserTesting system. Pay attention to not just what they say, but also their tone and level of enthusiasm. They have fundamentally different experiences of the same product.

- A common rule of thumb in the tech industry is that for a product to succeed, 40% of its users should be in the Dedicated group. So AI chatbots are currently far below the usual metric for a successful product category. In this sense, the hype for AI chatbots exceeds the reality. However, that’s not the full story…

The effect of AI chatbots on business productivity may be massive. The Dedicated AI chatbot users claim they are saving more than an hour of work every day. If true, that’s a stunning increase in productivity. It would be easy to dismiss these users as fanatics who don’t represent reality, but many of them are mid-career professionals who can give extensive details on exactly how they’re using AI chatbots and what the benefits are. If they’re right, most of us are probably still underestimating the ultimate impact of AI chatbots on business. That makes our next finding especially important…

UPCOMING WEBINAR

Effective AI: how to choose the right generative AI features—and build them fast

In this webinar, you'll learn new AI best practices, including:

- How the conversational interface is changing the way people interact with technology

- How to optimize AI for emotional impact and credibility, not just usability

- How you can make AI functionality more discoverable, increasing user adoption

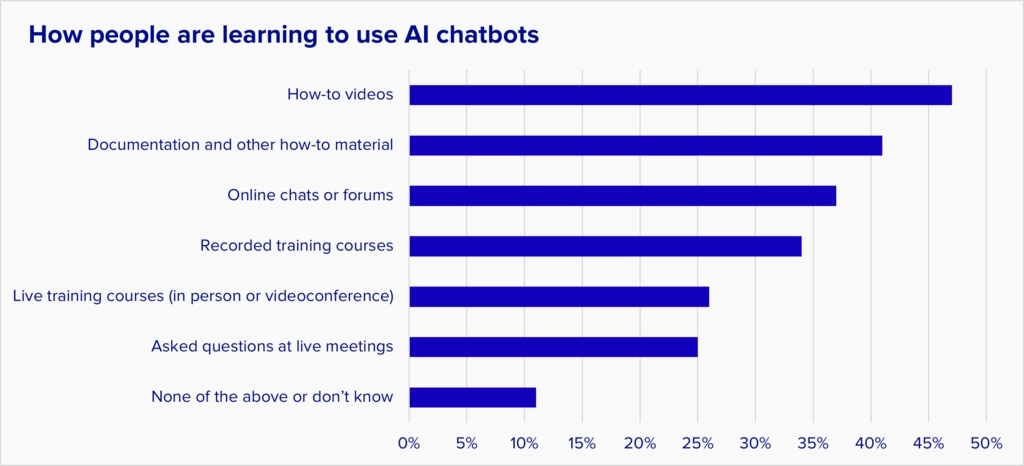

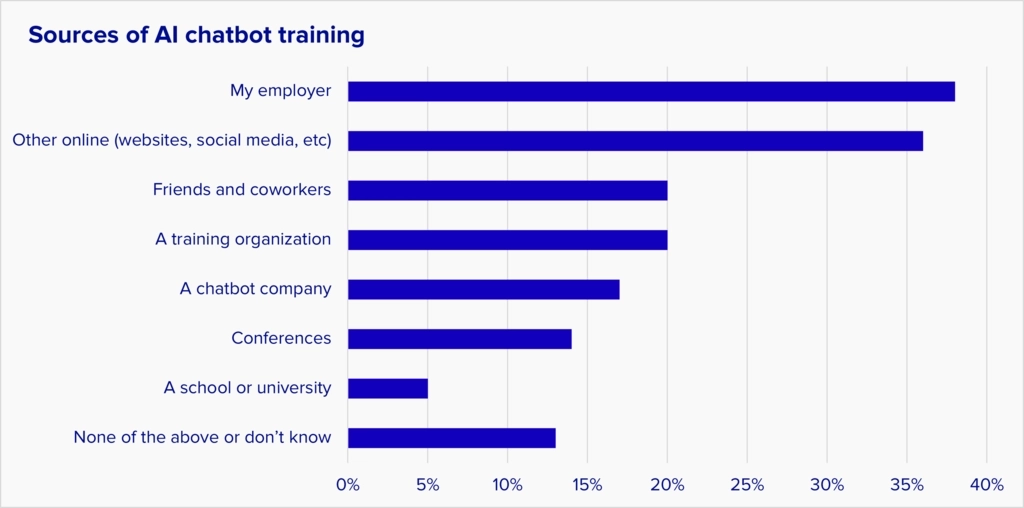

- Most employers are not being systematic about their use of AI chatbots. Most employers have treated AI chatbots as a security problem to manage rather than a productivity improvement to seize. Most AI chatbot users report that their employers passively allow them to use AI chatbots but do not heavily encourage them or say how to use them. Two-thirds of AI chatbot users didn’t receive any chatbot training from their employers, and the training from the AI chatbot companies is not reaching most users.

- ChatGPT is by far the dominant AI chatbot. More than 80% of AI-using knowledge workers have a free or paid account to ChatGPT. That’s far ahead of any other AI chatbot. To many people, the name ChatGPT is synonymous with all AI chatbots.

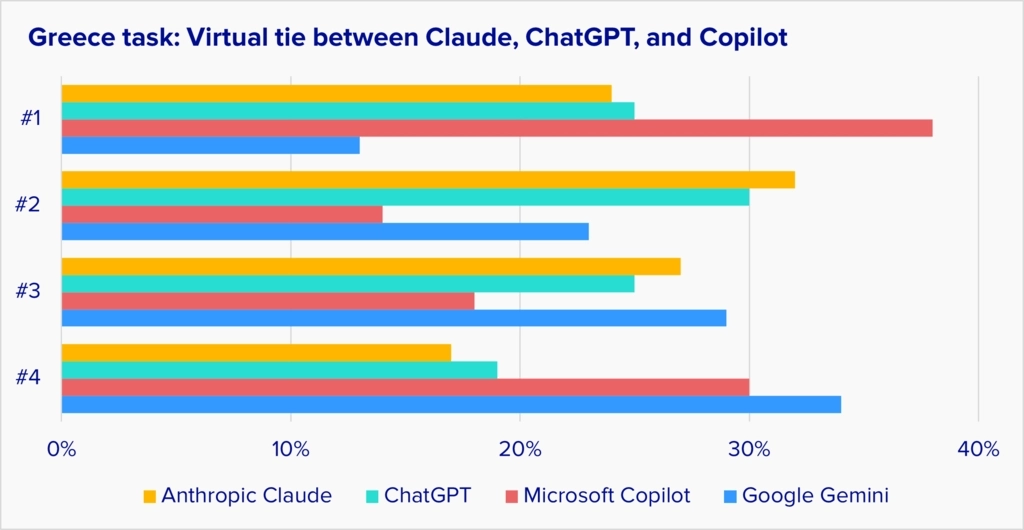

- People react to conversations with AI chatbots the same way they react to conversations with human beings. Small differences in tone, word choice, and formatting make a big difference in preferences, and people can even become insulted by a chatbot if they feel it shows the wrong “attitude.” We saw this strongly when we tested user reactions to AI chatbots. We gave the same questions to four of the leading bots, showed the anonymized answers to users, and asked them to stack rank the responses. Anthropic Claude scored highest because its answers gave the best mix of personable language and clear formatting. Microsoft Copilot was the most polarizing product— it received a lot of first-place votes and almost as many last-place votes. Copilot mingles AI responses and web search results in a unique way that some users love and others dislike

What companies need to do

- For companies making AI chatbots: think hard about adoption and differentiation. Why are only 20% of AI chatbot users deeply dedicated to their use? Our study showed that the AI chatbot creators have failed to fully explain their product to most users. The Dedicated users figured out on their own how to use AI chatbots as a generalized personal assistant. But the other 80% of users haven’t figured it out, and no one has taught them otherwise. This is the biggest barrier to further chatbot growth: The vendors need to show people the full range of problems they can solve with AI, and exactly how to change their workflows.

- The huge momentum behind ChatGPT will make it hard for other AI chatbots to get traction, especially because many users say all AI chatbots seem alike. Competitors should be thinking about how they can differentiate. Should they personalize their products for individual needs? That’s what many Dedicated users are asking for. Or should they shoot for a differentiated experience like Copilot, which pleases some users and displeases others?

- For companies adding AI features to their products, focus on business value and sweat the details. User reactions to the AI chatbot leaders point to important lessons for any company adding generative AI features to its products:

- Pay close attention to the tone and formatting of your responses. Most companies are used to testing their software for usability, but in the AI world, they also need to test for tone and credibility. What does your brand sound like in a conversation? What sort of things would it normally say, or not say? Previously, those questions were only issues for the marketing team, but generative AI chatbots now literally speak for the company. If the tone and word choices used by a bot are wrong, they won’t just hurt the product. They can also damage the brand.

- Show people how to transform their workflows. The AI chatbot pioneers were naive to assume that people would figure out on their own how to take advantage of the bots’ power. That works for a few users, but the rest need to be helped along. If your AI features require a change in the work habits of your customers, you need to be very clear about the benefits, exactly what they need to change, and how to do it.

- We discussed this issue with Forrester analyst David Truog, who added this perspective: Because people have differing expectations and fears about AI, it’s important that AI-based products adapt to user expectations and don’t overhype themselves. A product that gives friendly advice and presents possible answers to users is likely to go over a lot better than one that is assertive about declaring a single absolute truth.

- For companies deploying AI chatbots to employees: get serious about productivity. Most companies have focused their internal management of AI chatbots on preventing security risks. That’s appropriate, but they should also focus even more intensely on how they can proactively deploy AI chatbots to increase productivity. Although we noted above that AI vendors need to take responsibility for teaching users what to do with AI chatbots, a company that wants to be a productivity leader shouldn’t wait for a vendor to solve its problem. If the Dedicated users are correct about their productivity, rapid adoption of AI chatbots may be a decisive strategic advantage for companies that pursue it aggressively. It’s risky to hold back.

A note on the research: This information is based on a survey and interviews of more than 2,500 knowledge workers (people who use computers in their work more than two hours a day) in the US, Canada, UK, Australia, and Singapore. Data was collected in September-October 2024. For more details, see the section on Methodology at the end of this report.

The market

About 60% of knowledge workers use AI chatbots for work

In the five countries we surveyed, about 97% of knowledge workers have heard of AI chatbots, and about 60% use them at least occasionally in their work.

“Choose the phrase that best describes your use of generative AI chatbots in your work.” Base: All knowledge workers.

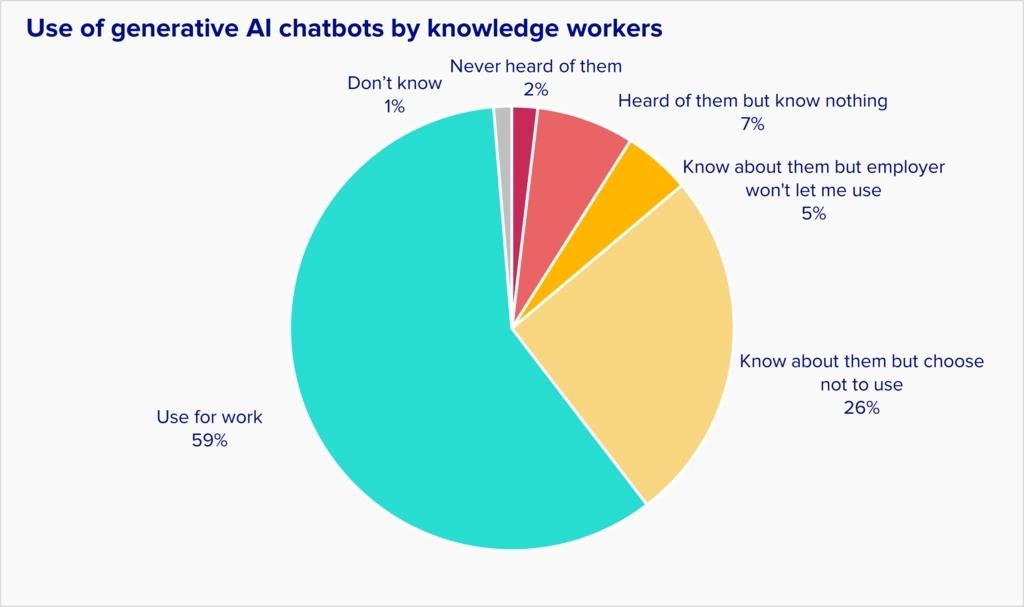

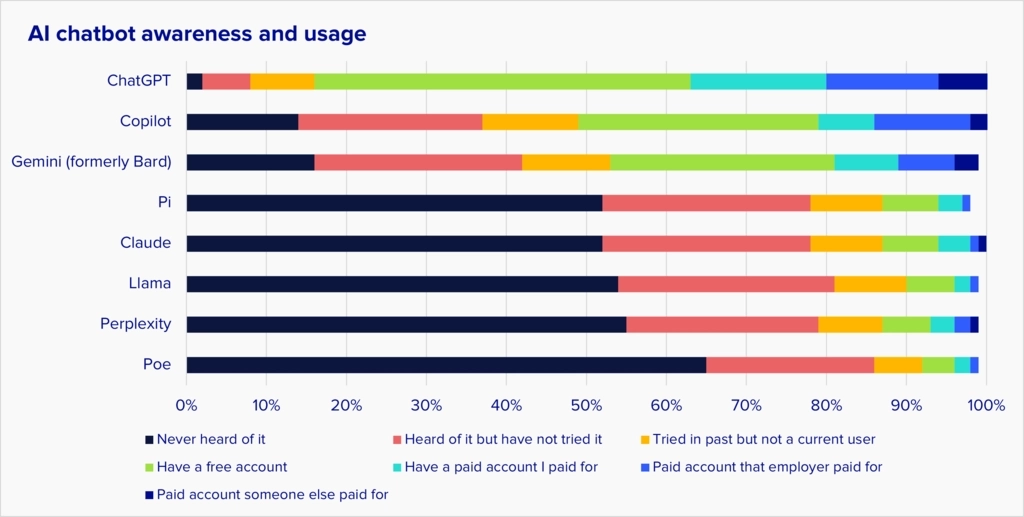

Why do some knowledge workers choose not to use AI chatbots? The overwhelming reasons are that they feel they don’t need it or it’s not relevant to their work. Only about 7% of knowledge workers say their employers forbid them from using AI chatbots. Here are their answers:

“Why haven’t you used a generative AI chatbot in your work? (choose all that apply)” Base: knowledge workers who don’t use AI chatbots for work.

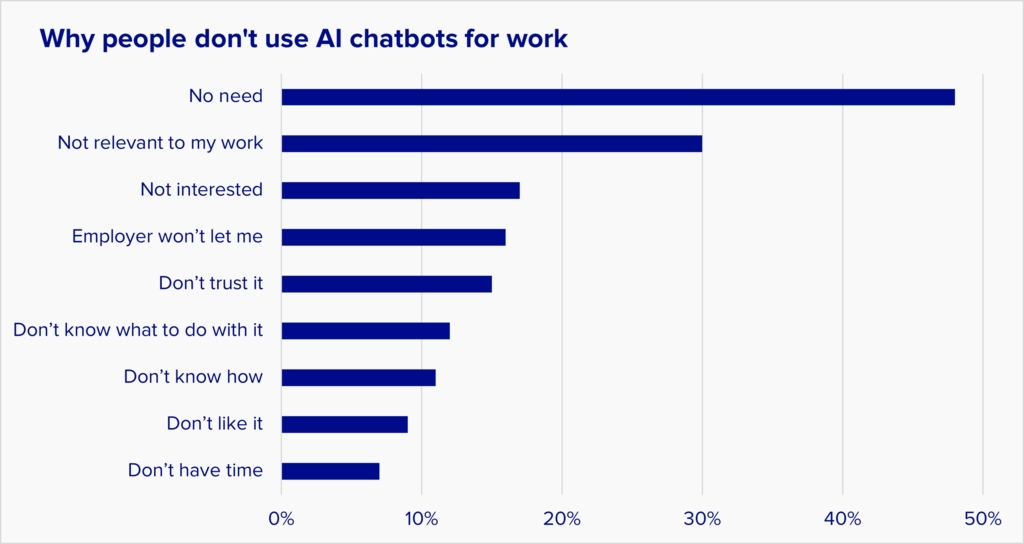

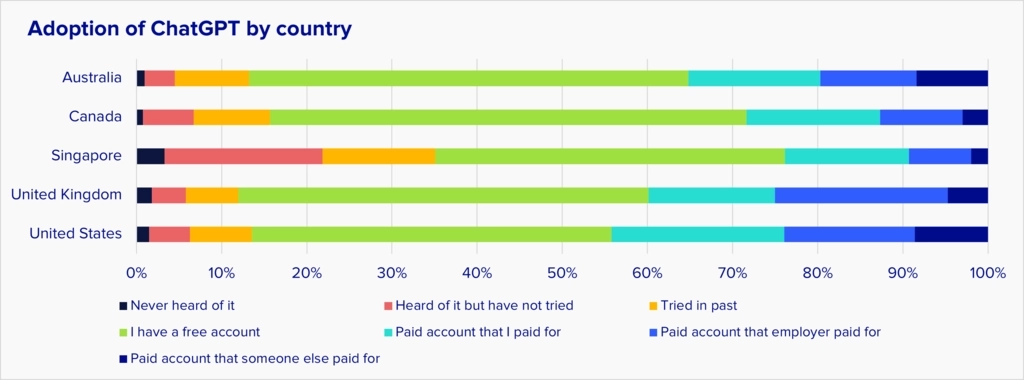

ChatGPT dominates awareness and usage

Chat GPT has by far the highest awareness and usage of AI chatbots.

- More than 95% of knowledge workers who use AI chatbots have heard of ChatGPT

- About 85% of them have accounts in ChatGPT:

- A third of AI-using knowledge workers have a paid account

- Another 50% have free accounts.

- ChatGPT’s name is so pervasive that some users use it as the term for the whole product category. They’ll use phrases like “things like ChatGPT” when referring to all generative AI chatbots.

Microsoft Copilot and Google Gemini are roughly tied for second place behind ChatGPT; about half of AI-using knowledge workers have accounts. The other AI chatbots are all far behind in both awareness and usage.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work.

How AI chatbots are used: the mystery of the indifferent users

AI chatbots are still looking for product-market fit

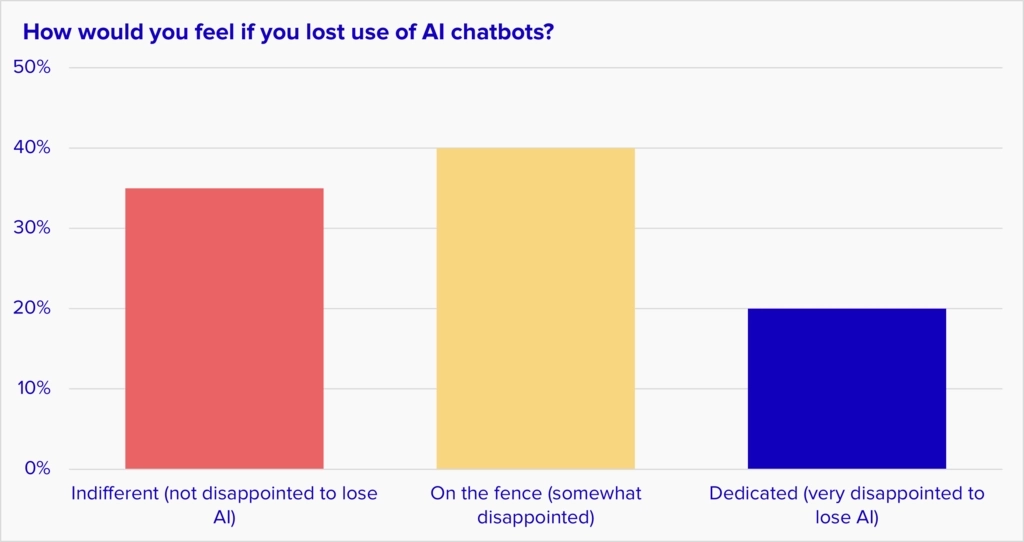

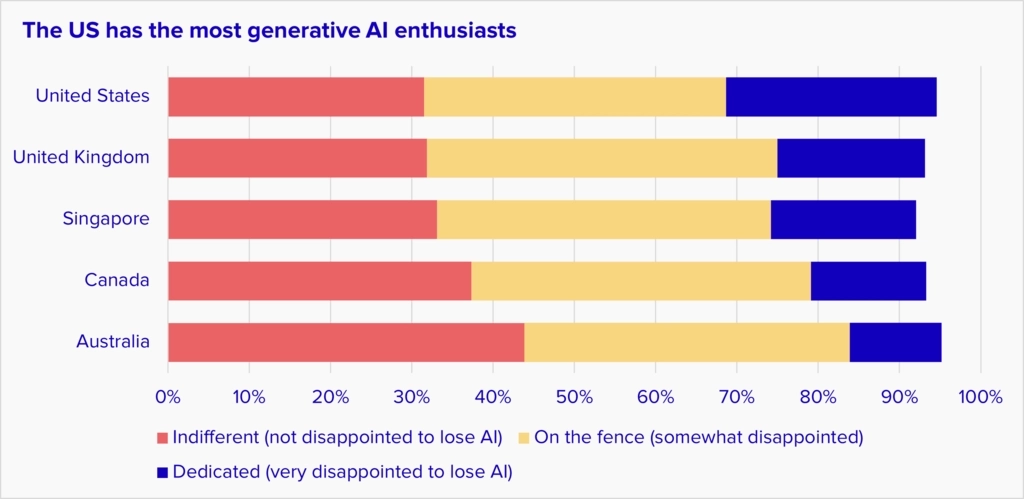

Although awareness and usage of AI chatbots is high, the users are very stratified. Some users are deeply passionate about AI chatbots, but most are relatively lukewarm about their importance. A popular test created by growth hacker Sean Ellis measures a product’s “product-market fit” by asking users how they would feel if they could no longer use the product. If fewer than 40% of users say they would be “very disappointed” to lose the product, it generally struggles to get market traction.

AI chatbots currently score far below the 40% threshold:

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work.

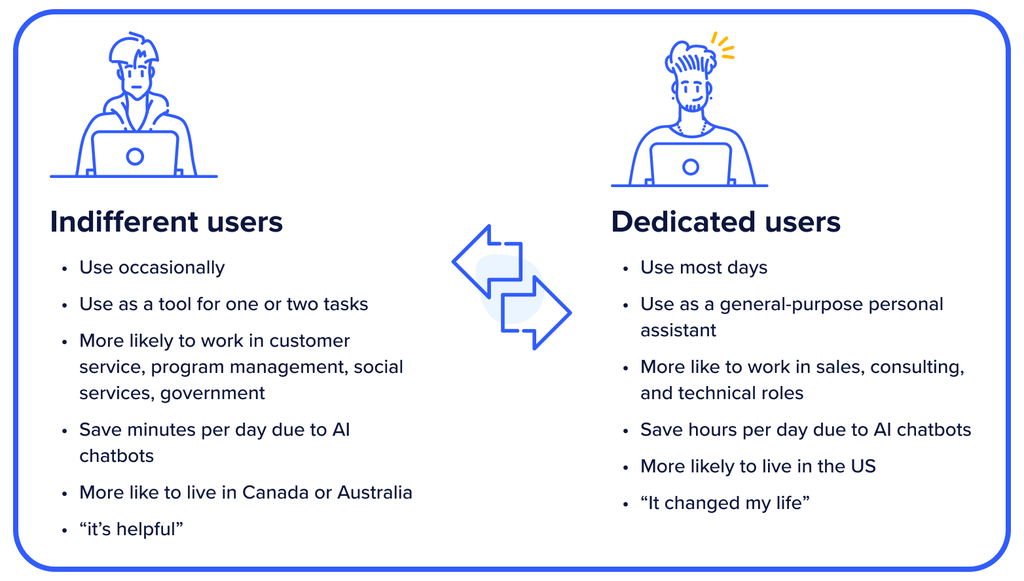

The differences between the Dedicated 20% and the Indifferent 35% are striking. Dedicated users are far more passionate about AI chatbots, use them for a wider variety of tasks, use them more often, and claim higher productivity gains from them.

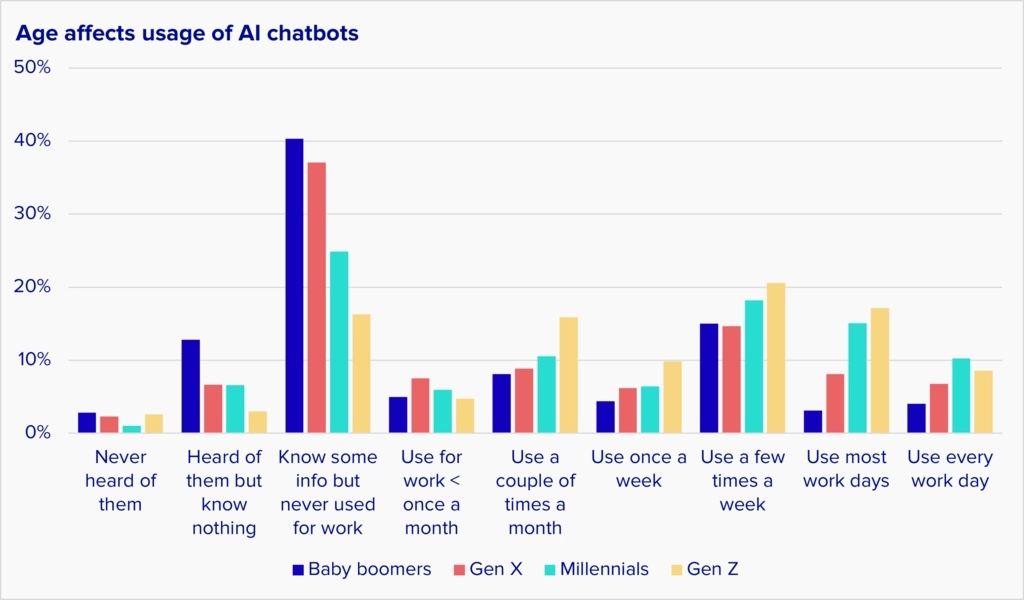

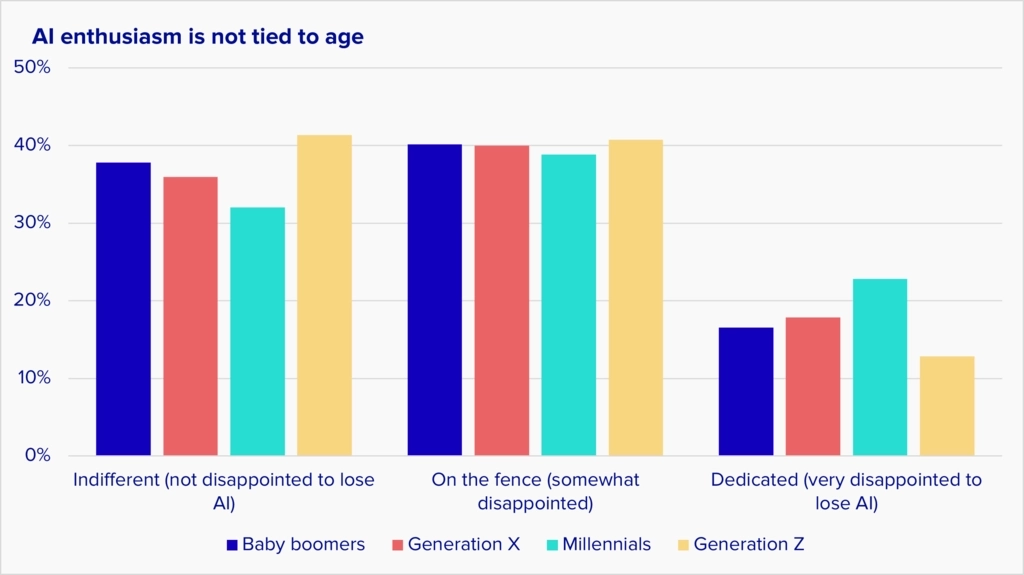

We wondered if age might also be driving the difference between Dedicated and Indifferent users. A common stereotype is that younger people are more enthusiastic about adopting new technology. It turns out that age does play a role in AI chatbot usage, but not the role you might expect.

As the chart below shows, about 40% of Baby Boomer knowledge workers know something about AI but have never used it for work. Generation X is similar, at about 37%. By contrast, only 16% of Generation Z knowledge workers know something about AI chatbots but haven’t tried them for work. So younger people are more likely to give AI chatbots a try.

However, that’s only half the story. Once they have tried AI chatbots at work, there’s no difference in enthusiasm level between the generations. Baby Boomers are just as likely to be Dedicated users as Gen Z.

We didn't expect this result, but it was confirmed by the video interviews we did with AI chatbot users. In the interviews, we found many mid-career professionals, normally cautious and cynical, who are giddy about what they do with AI chatbots.

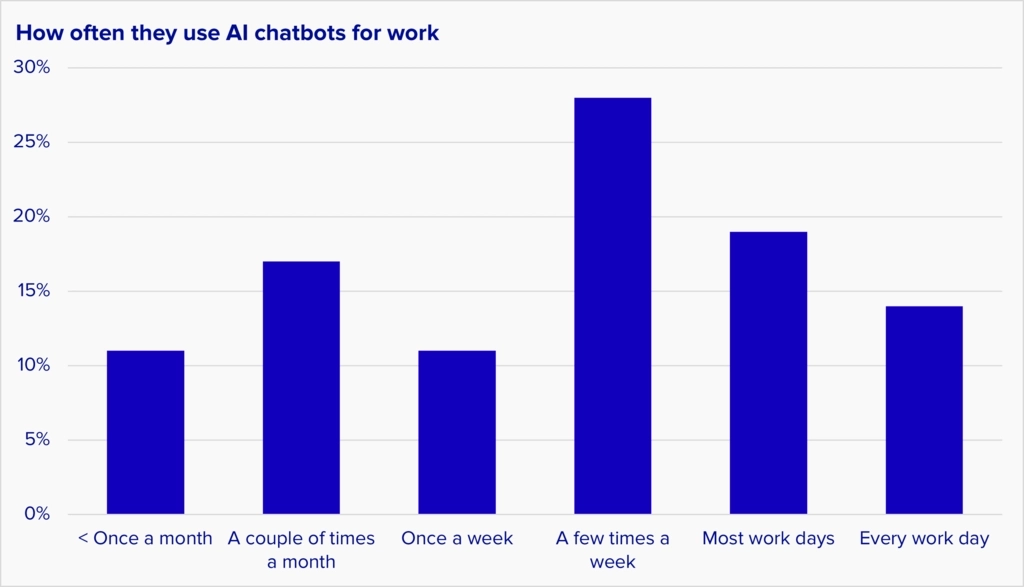

Frequency of AI chatbot usage varies from very heavy to very light

Along with stratification by enthusiasm level, AI chatbot users are also very stratified by their volume of usage. Many people who have access to AI chatbots almost never use them, while others use them every day:

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work.

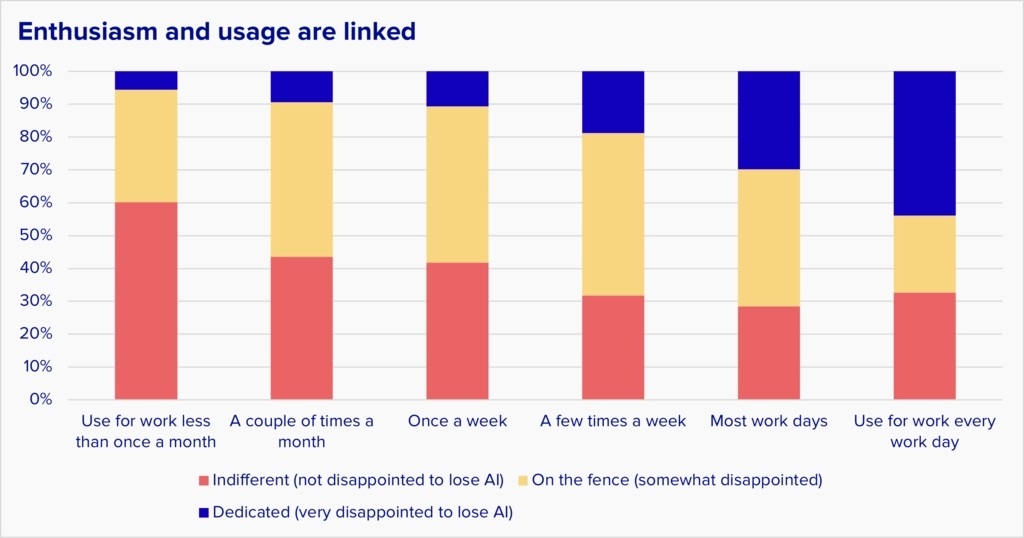

We cross-referenced those usage levels with enthusiasm level. As you might expect, the people who are most enthusiastic about generative AI also use it the most: 42% of the people who use AI chatbots every day are Dedicated users:

Share of enthusiasm within each usage group. Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work.

We were surprised that a fair number of On the fence users and Indifferent users were also frequent users. That means there is a fairly large contingent of people who are using AI chatbots frequently but don’t care deeply about the tasks they’re using them for.

It’s extremely unusual to see such high adoption for a product that so many people say has limited appeal. We think several things may be causing this:

- The intense publicity for ChatGPT pushed installation beyond what you’d typically see for a new product

- The current state of the art in AI chatbots makes them better for some job roles than others

- Most users are still learning to use AI chatbots, and they’ll become more enthusiastic about them once they learn more

Based on our interviews with knowledge workers, we think all three causes are in play.

What it means for companies

There are a couple of important lessons in this:

- Remember the Indifferent users. The phrase “AI” attracts a lot of customer attention, but if you’re looking to add it to your products, you need to be aware that there’s nothing magical about AI in and of itself. Saying that you have it in your product might drive some trial usage, but in order to attract lasting usage the technology needs to solve a business problem.

- The AI chatbot vendors need to answer two questions urgently:

- Exactly what makes the Dedicated users different? Are they just enthusiasts, or is there something else about them that drives AI usage?

- Can the Indifferent and On the fence users be turned into Dedicated users? If so, how?

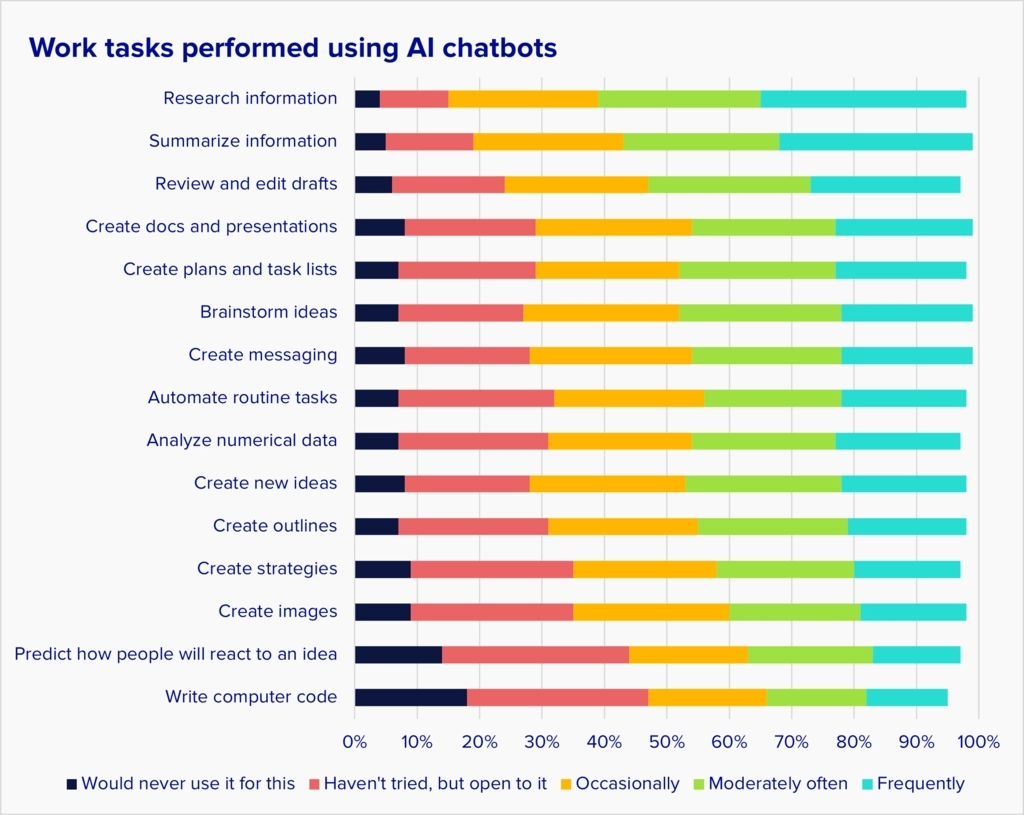

Researching and summarizing information are the most common AI chatbot tasks

Information collection and processing are the most common tasks performed with AI chatbots for work. About a third of users said they use AI chatbots to do that frequently. The least common tasks were predicting human reactions to a new idea, and writing computer code. Coding is probably a low-instance use because most people do not program as part of their jobs.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

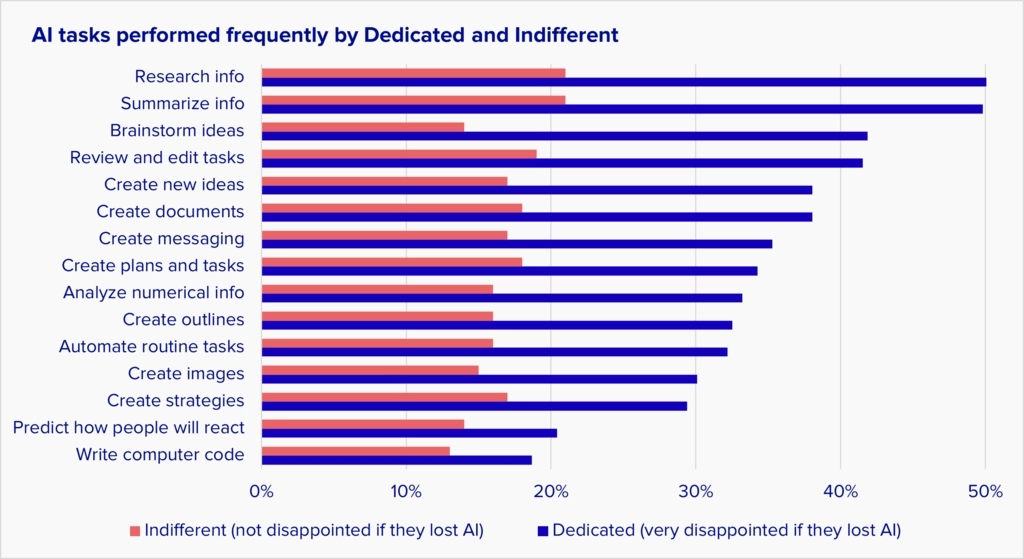

This chart mixes together people at all levels of AI enthusiasm, so we wanted to look at the most and least enthusiastic users separately. The chart below shows the percent of Dedicated and Indifferent users who say they frequently perform various tasks with AI chatbots. As you can see, there is a huge difference in usage overall. The difference is especially large for brainstorming ideas.

One of the biggest things that distinguishes the Dedicated users is that they’re treating AI chatbots like generalized personal assistants, while the Indifferent users tend to treat them as tools for specific tasks.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

The #1 benefit of AI chatbots is saving time

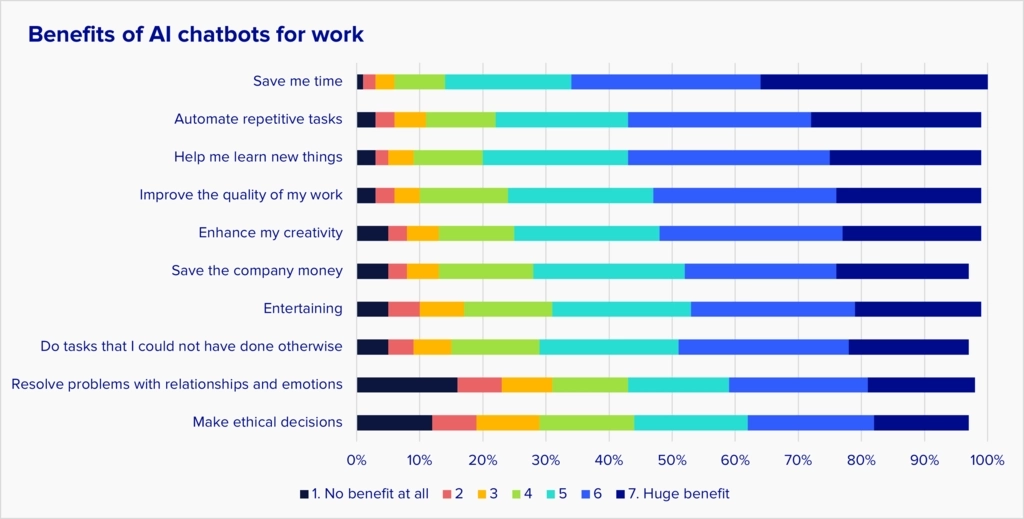

There are many claimed benefits for AI chatbots in work. We asked users to tell us which ones are most important to them. Saving time was ranked at the top, followed by automating repetitive tasks. The lowest-ranked benefits were intensely human-related: solving relationship problems and making ethical decisions.

“How much benefit, if any, are you getting from using generative AI chatbots in your work?” Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

The time savings from AI chatbots are substantial

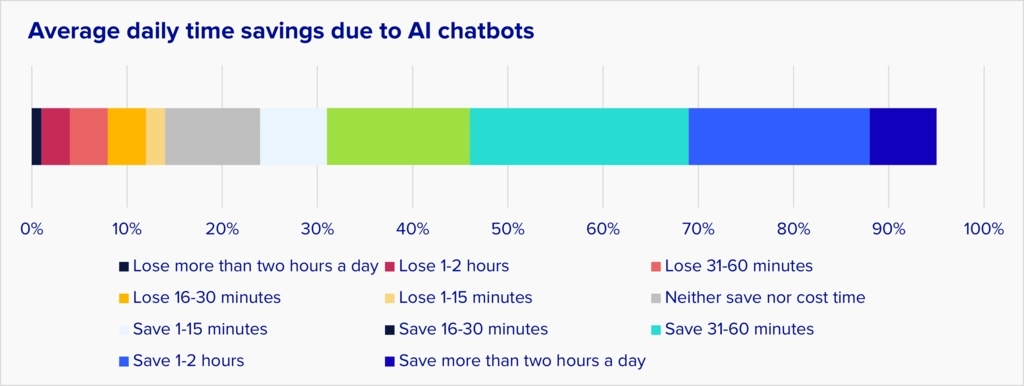

Since saving time was the #1 benefit, we asked AI chatbot users how much time they were saving. The results were impressive: half of knowledge workers said they’re saving 30 minutes or more per day due to AI chatbots.

Keep in mind that it is difficult for people to estimate time savings accurately, so these results should be viewed as preliminary. However, they are in line with findings from some other studies. For example, a Thomson Reuters survey in mid-2024 found that professional services workers are saving almost an hour a day due to AI chatbots.

But the picture isn’t rosy for everyone. About 15% of knowledge workers say the bots are costing them time, and another 10% say they are getting no time savings.

“In an average work day, how much time do you save or lose by using generative AI chatbots?” Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

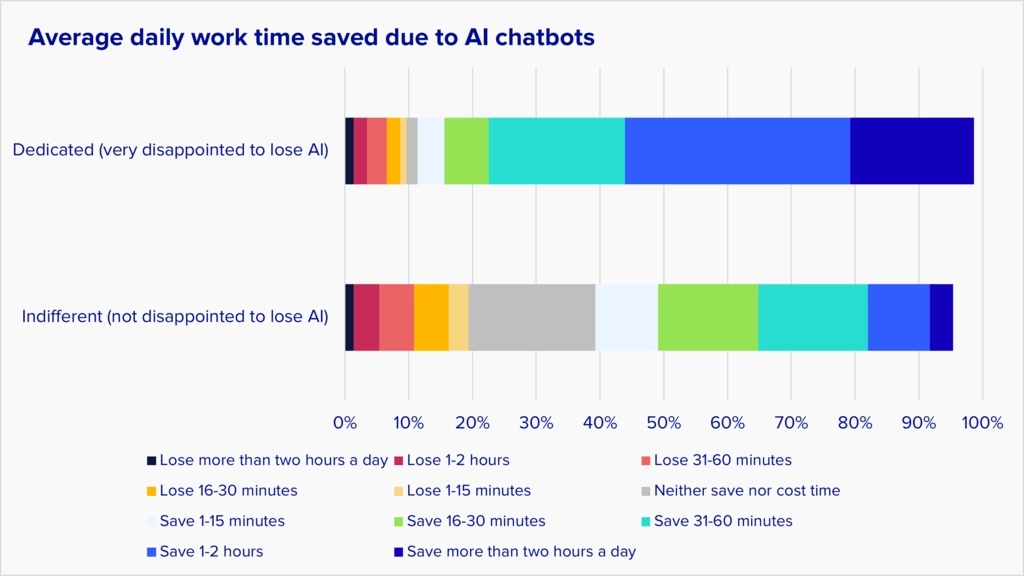

When we break out the enthusiasm groups, you can see that time saved is one of the starkest differences between Dedicated and Indifferent users. More than half of the Dedicated say they’re saving an hour or more a day, while only about 15% of the Indifferent say they’re saving that amount of time.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

The time savings claimed by Dedicated users are very impressive. If true, they are the sort of thing that can boost national productivity levels.

The tech industry has in the past often struggled to measure its impact on productivity. In the late 1980s, economist Robert Solow said,

“You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”

In 2018, the consulting firm McKinsey said a similar problem existed with digital transformations.

Remarkable claims need remarkable evidence, so the effect of AI chatbots on productivity needs to be studied much more heavily, with controlled experiments rather than self-reported benefits.

Nevertheless, there’s enough evidence of increasing productivity that companies should be thinking very deeply about how they can deploy AI chatbots aggressively in their workflows. The evidence from our survey shows that most employers are not taking AI chatbots as seriously as they should. We give more details on that in the Governance section below.

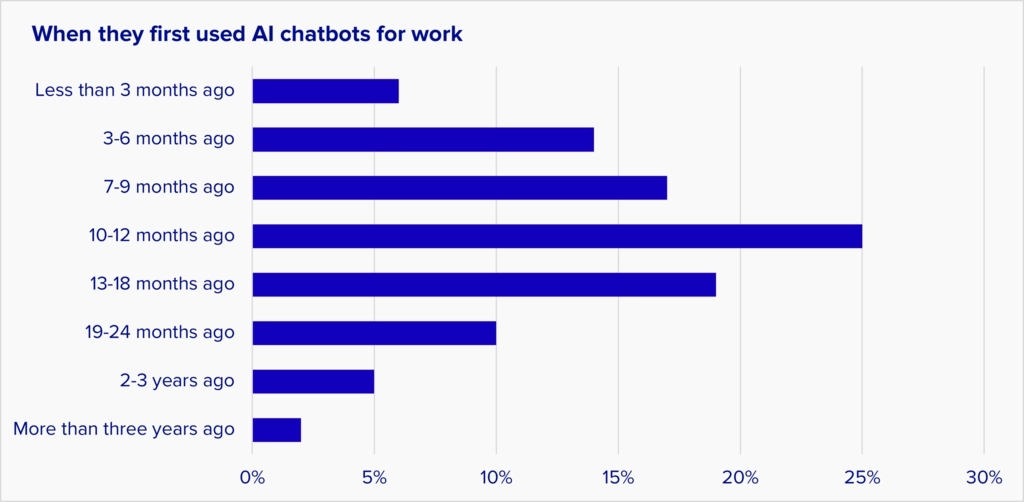

Most business users of AI chatbots started in the last year

AI chatbot usage is still very young. About 60% of AI chatbot users in business started using them within the last 12 months. The rate of new adoption dropped recently because there are relatively few additional knowledge workers left to try it in the countries we studied.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

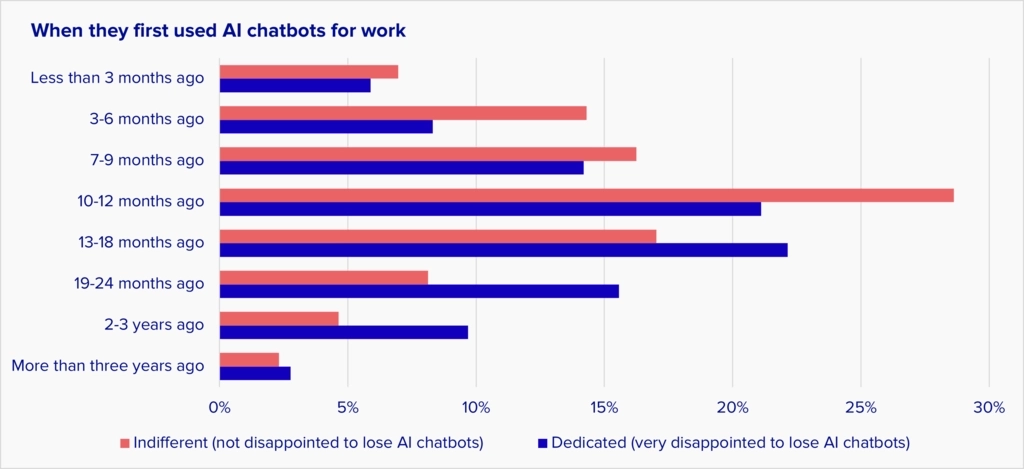

Looking at the adopter groups (below), the Dedicated started using AI chatbots for work a bit earlier than the Indifferent. The peak in adoption among Dedicated came about six months before the peak of the Indifferent.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

At first glance, that’s not surprising – people who were enthusiastic about AI chatbots tended to use them early. However, that’s not the full story. About a third of the Indifferent have been using AI chatbots for more than a year, and more than a quarter of the Dedicated started using them in the last nine months.

So the Dedicated are not just early adopters, and the Indifferent are not just late adopters. There’s something different about the Dedicated that is not tied to the adoption curve.

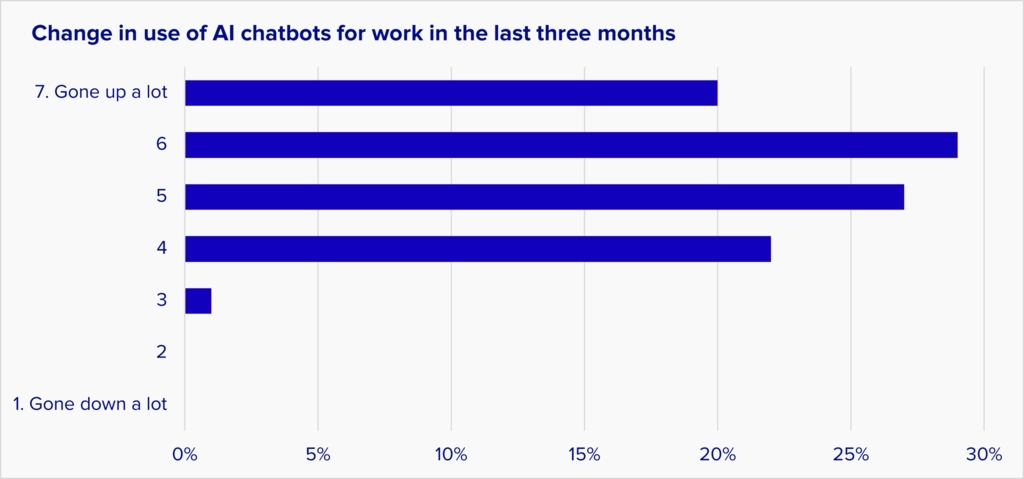

AI chatbot usage continues to grow

Although there isn’t much room to add more users in the countries we studied, usage is still growing fast. Over three-quarters of AI chatbot users say their usage grew in the last three months.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

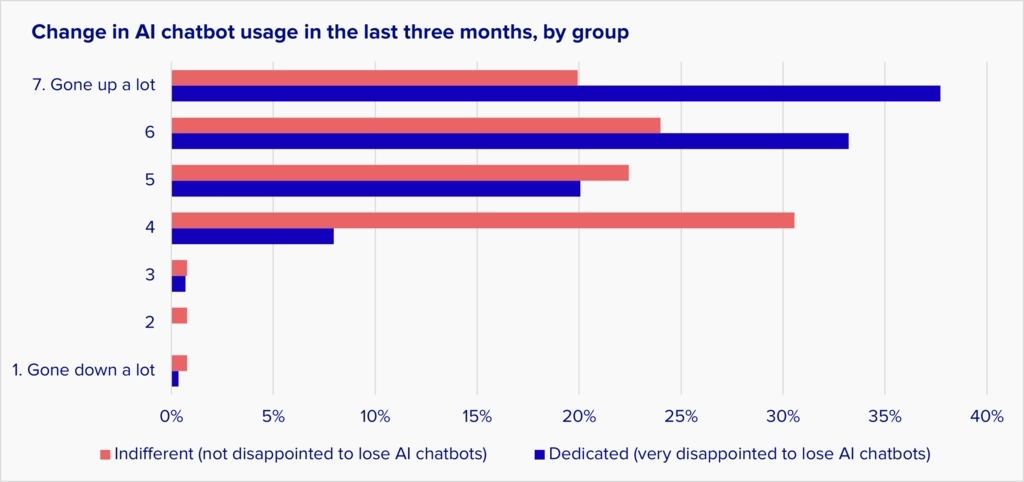

Usage by Dedicated users is growing strongly; about 90% of Dedicated say their usage grew in the last quarter. But even among the Indifferent, about two-thirds say their usage is growing.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

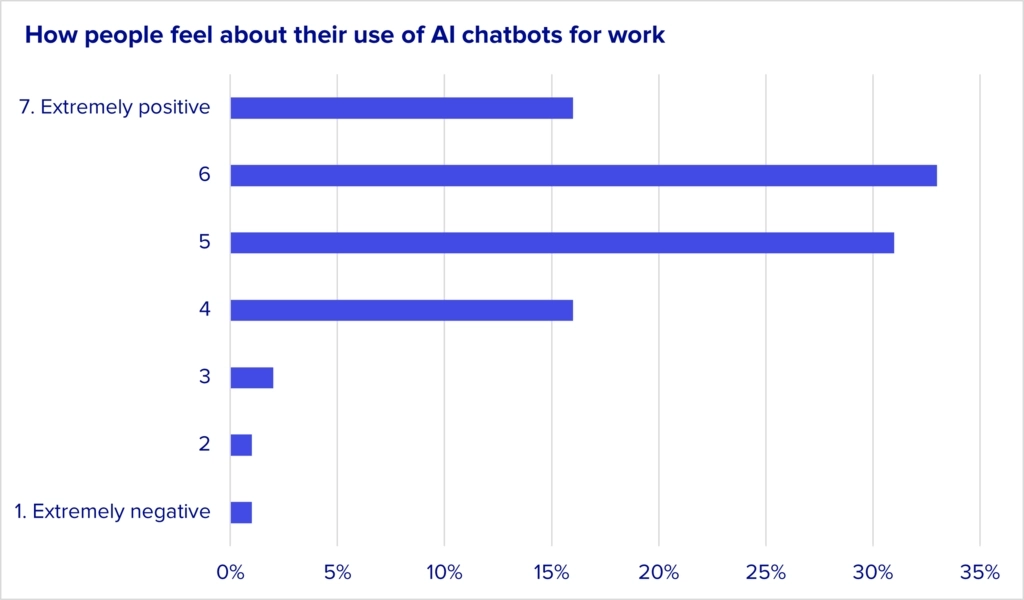

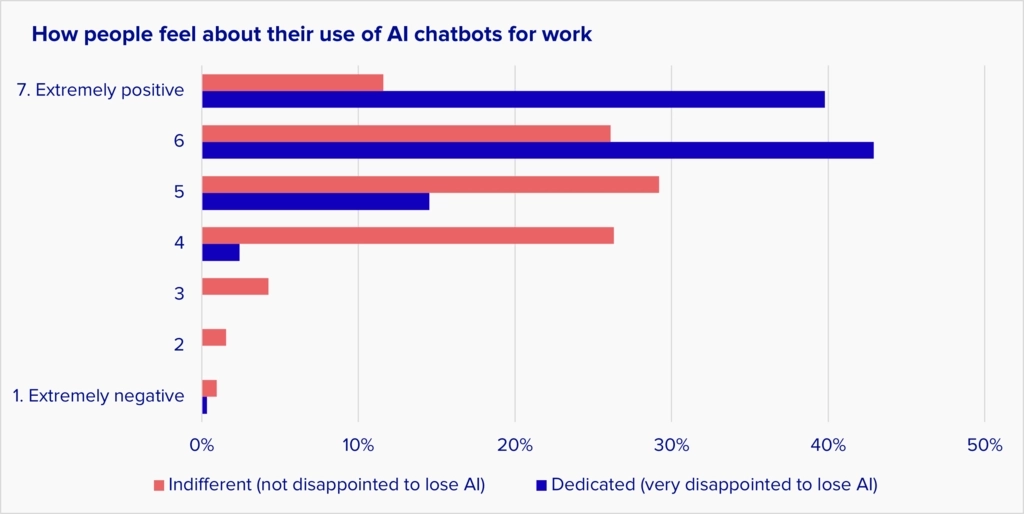

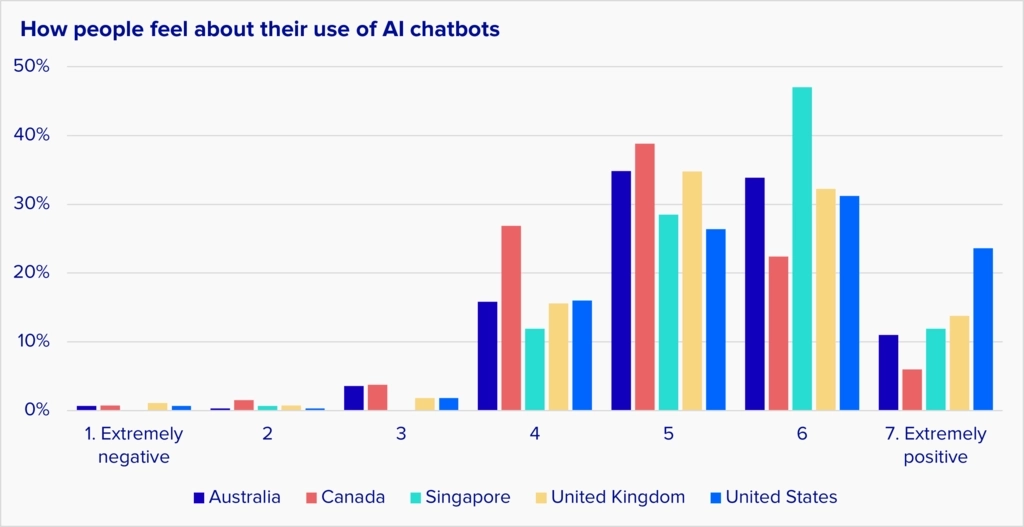

Most knowledge workers feel pretty good about their use of AI chatbots

We can all think of cases in which companies forced employees to use tech products that they didn’t like. That’s emphatically not the case with AI chatbots. About 80% of users feel at least somewhat positive about their use of AI chatbots for work, and only about 5% are negative about it.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

As you’d expect, the Dedicated feel very positive about their use of AI chatbots in work, while the Indifferent are much more measured in their point of view.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

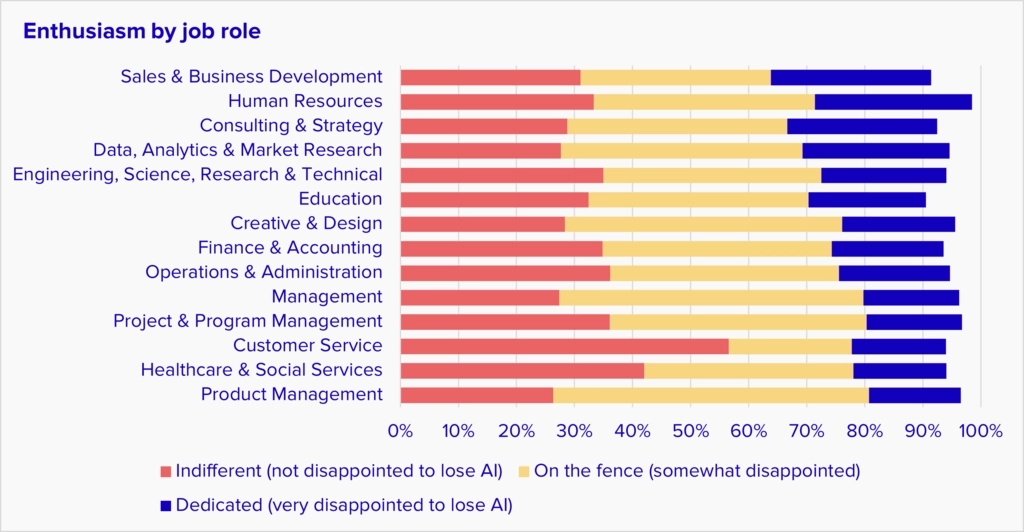

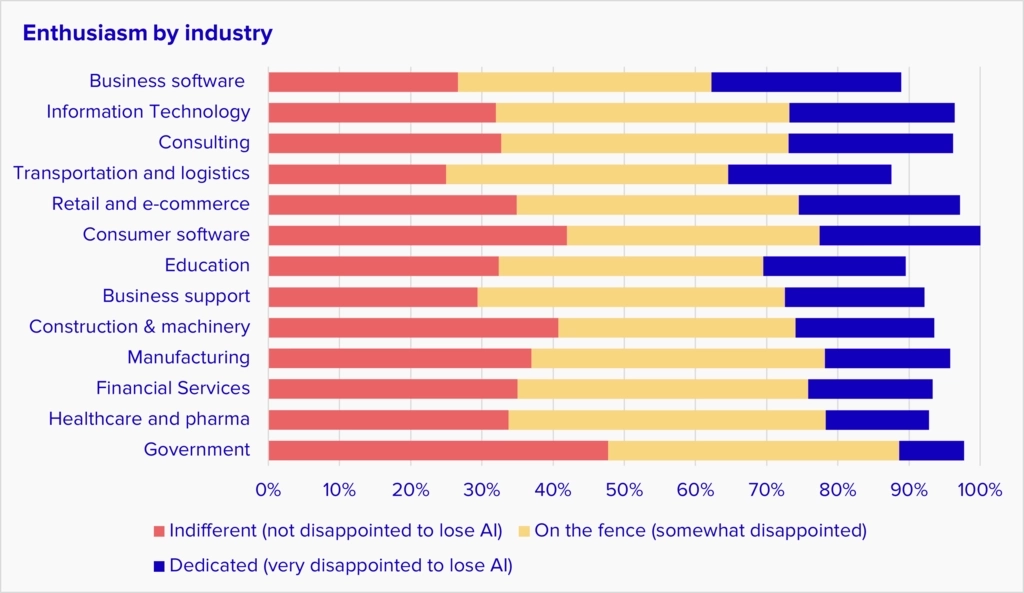

Is AI chatbot usage tied to a particular job role or industry? A bit.

We checked whether enthusiasm for AI chatbots correlated with working in particular job roles or industries. There’s a connection, but it’s fairly subtle.

When looking at job roles, the highest share of dedicated users is in sales, HR, consulting, and data analysis roles. All are made up of 25% or more Dedicated users. In contrast, Dedicated users are only 16% of product management:

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

There was a similar subtle pattern in industries. 27% of users in business software companies were Dedicated users, while only 9% were Dedicated in government:

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

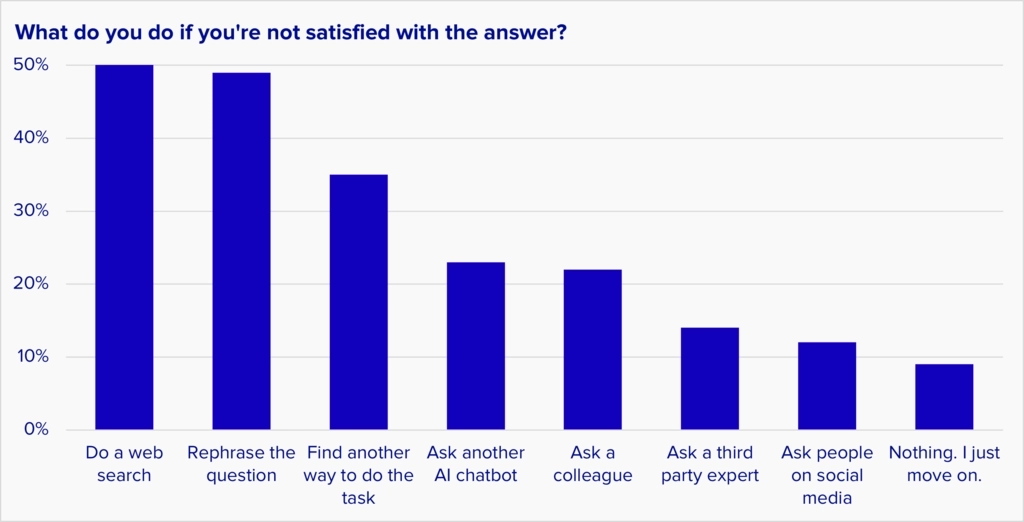

AI chatbots are rarely being used together

We asked people what they do when they’re not satisfied with the answer from an AI chatbot. We expected that many people would say they ask a different chatbot, but most often, people do a web search instead or rephrase the question and ask the same chatbot again. Only about a quarter ask a second chatbot.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

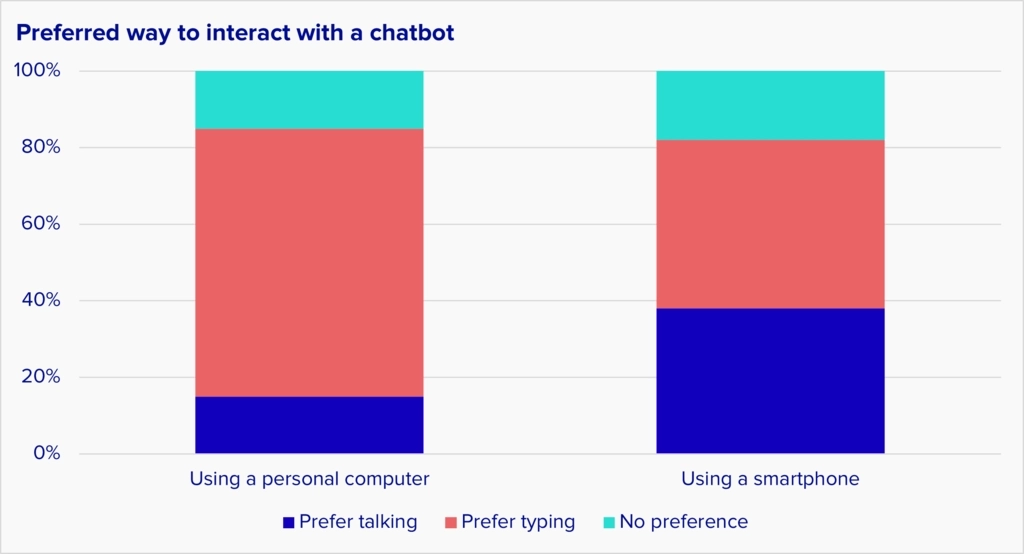

Smartphones may need a different chatbot user experience

Most people prefer using a keyboard to interact with an AI chatbot on a computer, but the story is different for smartphones. A narrow plurality of mobile users prefers typing, but almost 40% of users would prefer to be able to talk with the bot.

Companies adding chat-like AI features to their products need to be aware that it may not be possible to produce an optimal experience that spans across both computers and smartphones.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

National differences

The survey results in all countries were broadly the same, with a few exceptions:

- AI chatbot usage in the US was a bit higher and more enthusiastic than in some other countries, especially Canada and Australia.

- There are some country-specific complaints about the poor ability of AI chatbots to adjust to local culture and use of English. Here's what users said:

Here are the survey results:

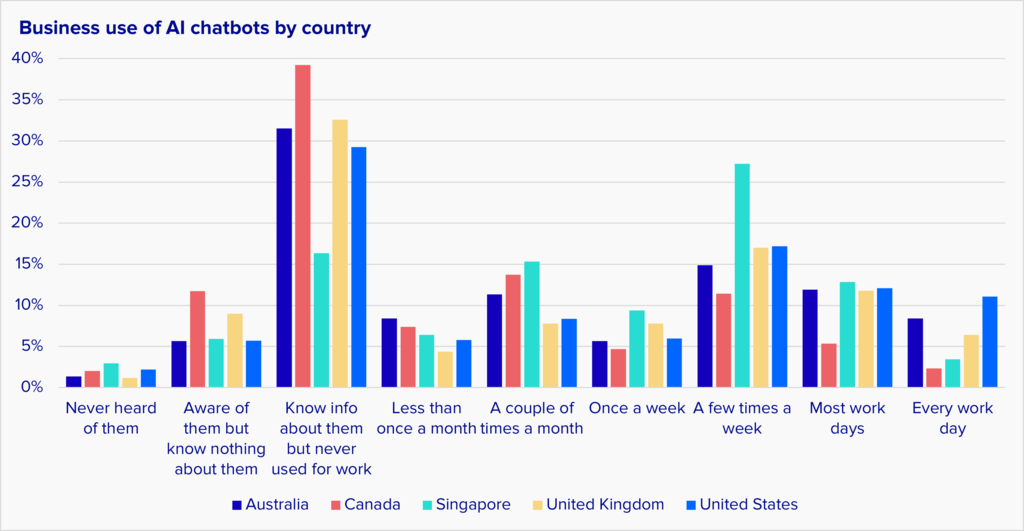

AI chatbot usage in Canada and Singapore differs from the other countries

The chart below shows the AI chatbot usage patterns of each country. The differences that stand out most are:

- The US had the highest share of heavy AI chatbot users; Singapore and Canada had the lowest. (11% of American knowledge workers use AI chatbots daily, compared to 3% in Singapore and 2% in Canada.)

- Singapore doesn’t have the most intense use, but it has the broadest. It has a huge group of moderate users (use a few times a week), and a much smaller share of knowledge workers who know about AI chatbots but have never tried them (about 15% compared to 30% everywhere else).

- Canadian knowledge workers were much more likely to report not using AI chatbots for work (53% of Canadians compared to 37% of Americans).

The US has the largest share of Dedicated users

Given the US's higher overall usage rate, it’s not surprising that the US also has the highest share of Dedicated users. About 26% of US generative AI users are Dedicated, more than double the rate in Australia.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work.

There were also differences in the adoption of specific AI chatbots. For example, although ChatGPT is the most popular AI chatbot in all the countries we surveyed, its presence varies. Americans were most likely to have a paid account, while Singaporeans were the least.

Another example is that the adoption of Copilot is lower than ChatGPT in all countries, but especially in Canada and Singapore.

Americans are the most positive about their use of AI chatbots, and Canadians are the least

We found no country where knowledge workers were negative about their use of AI chatbots, but there were differences in the level of positivity. 24% of American knowledge workers said they were extremely positive about using AI, while only 6% of Canadians were. Meanwhile, 27% of Canadian knowledge workers had neutral feelings about AI chatbots, compared to 16% of Americans.

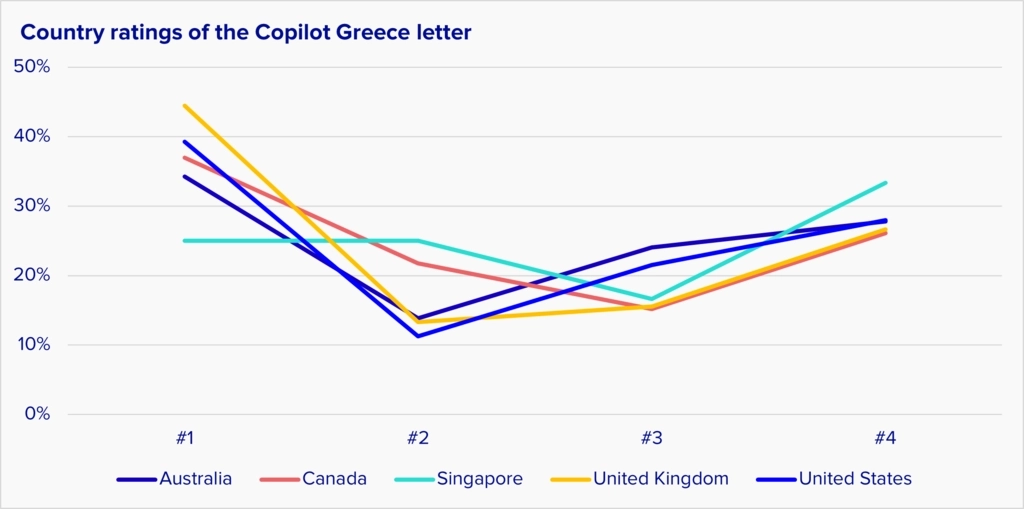

In our triathlon, countries rated the AI chatbots similarly

We checked our AI triathlon results to see if different countries reacted dramatically differently to the AI chatbots’ answers. We found the results were similar around the world. As an example, here’s how each country rated Microsoft Copilot’s email encouraging someone to visit Greece. While the results were not identical, the U-shaped curve – meaning people tended to either love or hate the answer – was present everywhere.

Base: knowledge workers in each country. Horizontal axis: rating of the chatbot’s response, from #1 (first place) to #4 (last place). Vertical axis: percent of users who gave it that rating.

Training and governance

Most people aren't formally trained to use AI chatbots

Most people are learning to use AI chatbots through online videos, how-to manuals, and chat forums.

“Choose the answer(s) that best describe the training you have received in the use of generative AI chatbots. Choose all that apply.” Base: All knowledge workers who use AI chatbots.

Here's how users described the situation:

The chatbot companies aren’t training most users

Most AI chatbot training is coming from employers and self-serve sources online. Training from chatbot companies, who have the biggest stake in educating users, hasn’t reached most of them.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

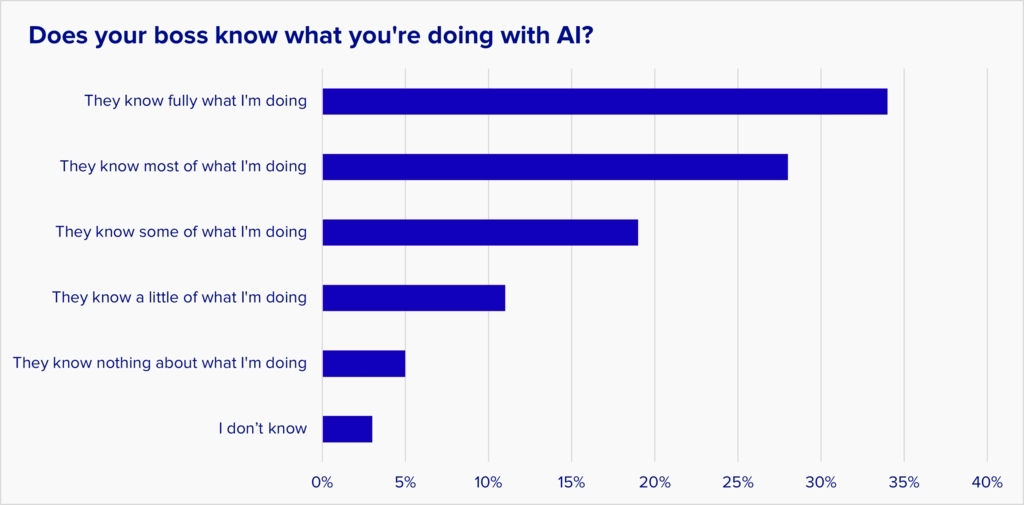

Employers know most of what’s being done with AI chatbots—but not all of it

Since so much business adoption of AI chatbots is driven by individuals, companies shouldn’t assume that they understand everything their employees do with AI. Most AI chatbot users say their bosses know most of what they’re doing with AI, but only about a third say management knows everything, and about 15% say management knows little or nothing about what they are doing.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

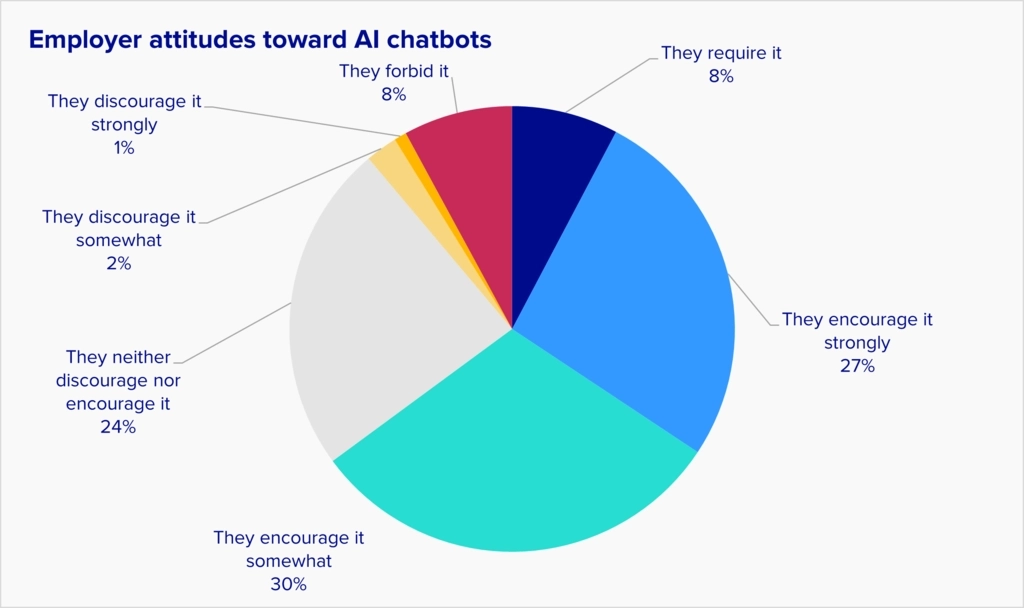

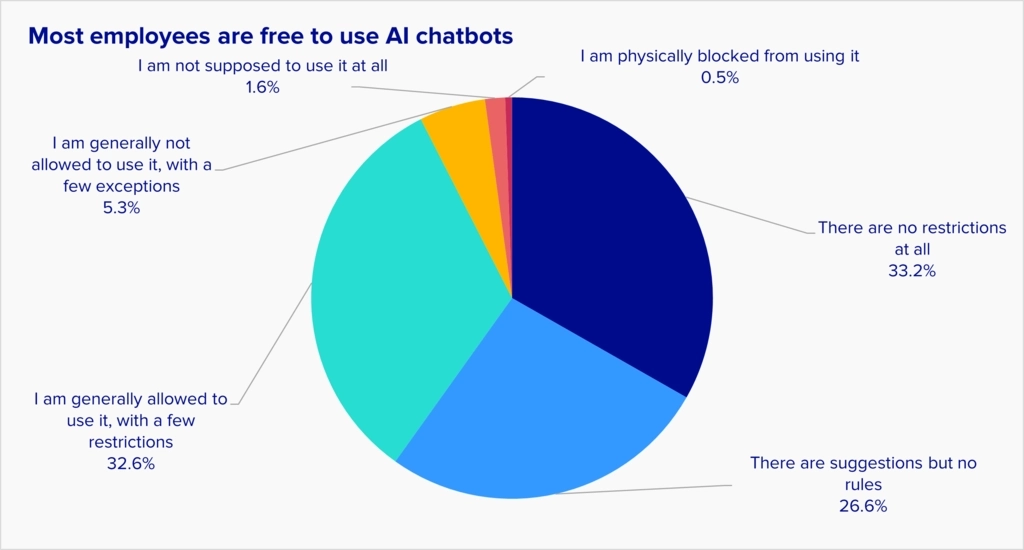

Few employees are required or forbidden to use AI chatbots for work

There have been high-profile reports of companies restricting employee use of AI chatbots, but our survey showed that’s not the norm. Most knowledge workers say their employer has a fairly hands-off attitude that allows chatbot use and sometimes encourages it but generally lets employees decide on their own what they want to do. Only about 9% of knowledge workers said there are strong restrictions on what they’re allowed to do with AI chatbots

We asked three questions related to this subject. First, what is management's overall attitude toward AI chatbots? Does it encourage or discourage their use? Almost half of knowledge workers said management is encouraging the use of AI chatbots at least mildly. Only a few percent said management was negative.

“Choose the phrase that best describes your employer’s general attitude toward the use of generative AI chatbots in your work.” Base: all knowledge workers who know their company’s policy.

The second question we asked was about management’s control over the use of AI chatbots. Are there any rules or guidelines? How restrictive are they? Most knowledge workers said that the rules, if they exist at all, are not very restrictive.

“Does your employer have official restrictions on the ways you can use generative AI chatbots for work? Please choose the answer that fits best.” Base: All knowledge workers who know their company's policy.

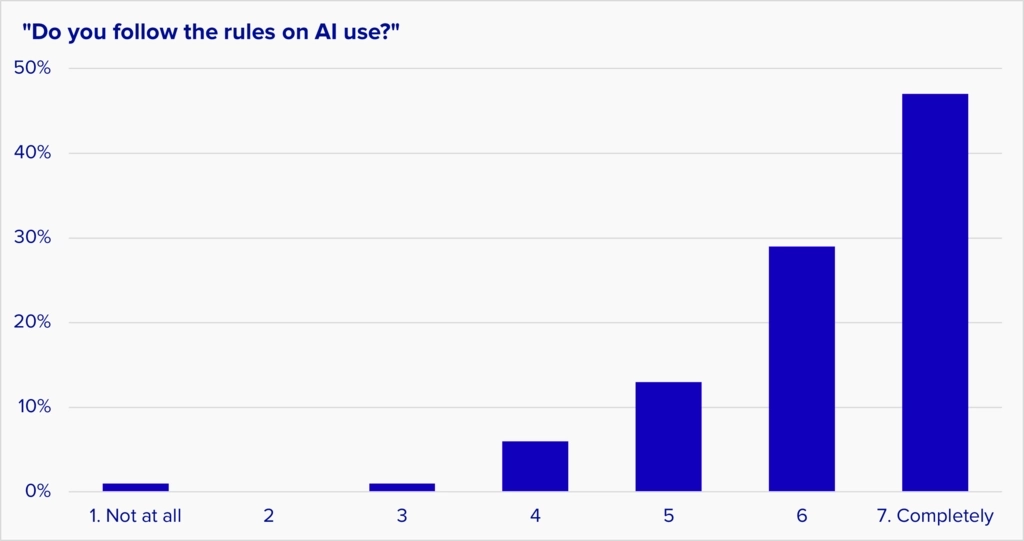

Finally, we asked knowledge workers if they follow their employers’ rules on use of AI chatbots. Managers may be relieved to hear that employees generally do follow the rules on use of AI. (We also double-checked to see if employees who have very restrictive rules are following them, and the answer was generally yes.)

“Do you comply with your employer’s rules on the use of generative AI chatbots in your work?” Base: All AI chatbot users.

Public attitudes toward AI and related issues

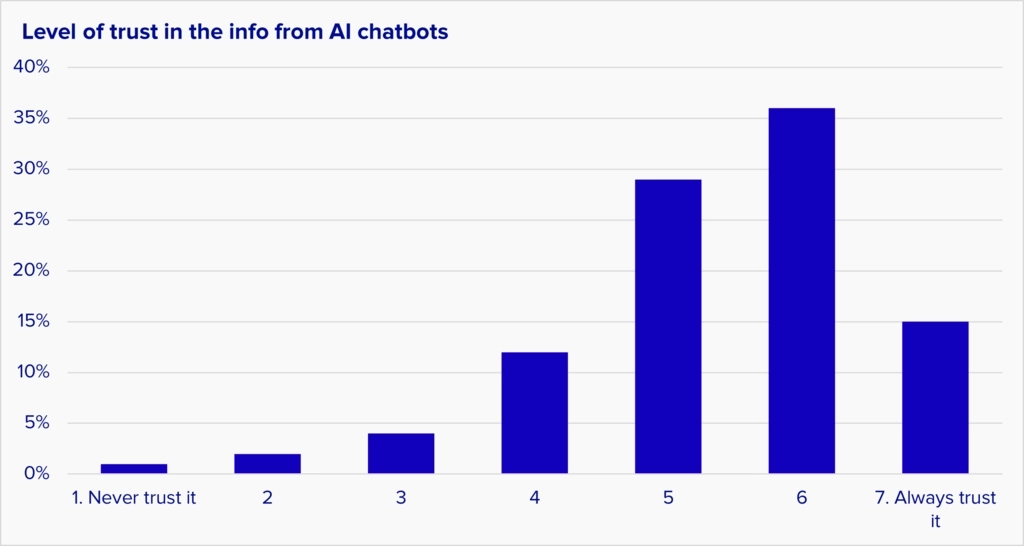

There's widespread trust in AI chatbots, but it’s not absolute

Given the many instances in which AI chatbots hallucinate, we were very curious to see how much people trust the information they get from AI chatbots. The answer is they have a fair amount of trust, but it’s not absolute.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

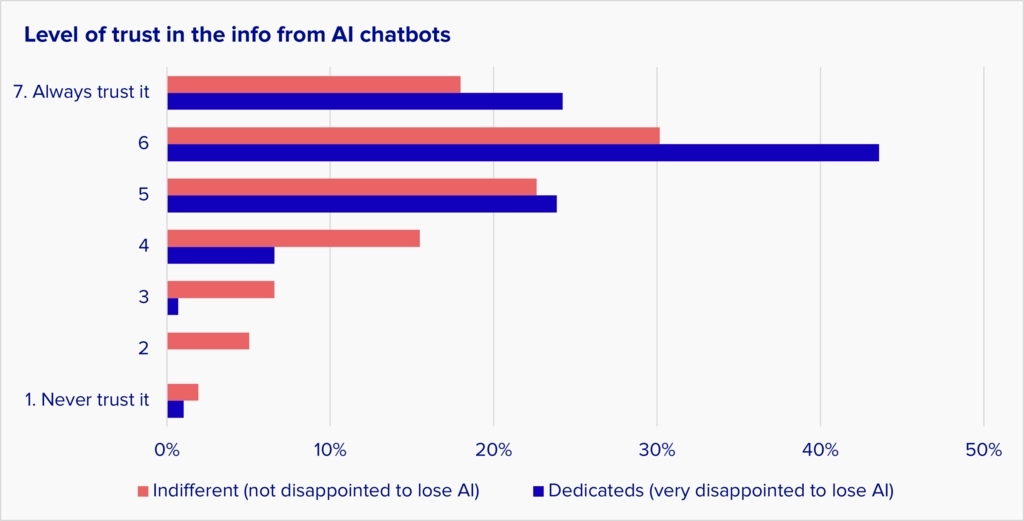

The Dedicated users have more trust in chatbot information than Indifferent users, but relatively few people in either group were willing to give it a top rating.

Base: knowledge workers who use AI chatbots for work

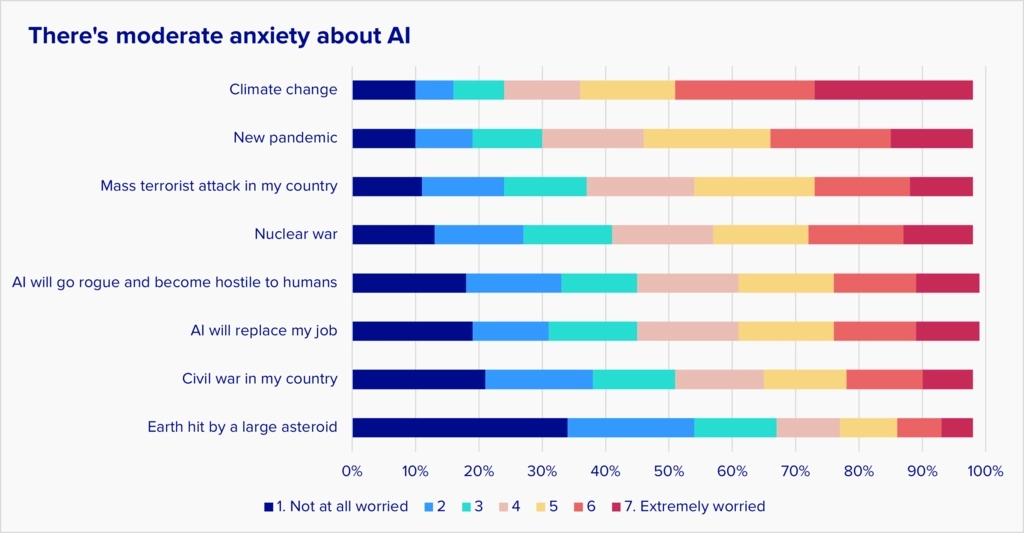

Most people aren't deeply fearful of AI

The fear of AI destroying jobs or going rogue has been discussed extensively in the press and online. We wanted to see how those fears are playing out in the minds of knowledge workers, so we asked them to rate various anxieties. About 20% of the population reports strong worries about AI (6-7 on a 1-7 scale), but most knowledge workers are more concerned about climate change and the risk of another pandemic.

“Looking ahead to the next ten years, how concerned are you about the following possibilities?” 1-7 scale, 7=extremely worried. Base: All knowledge workers.

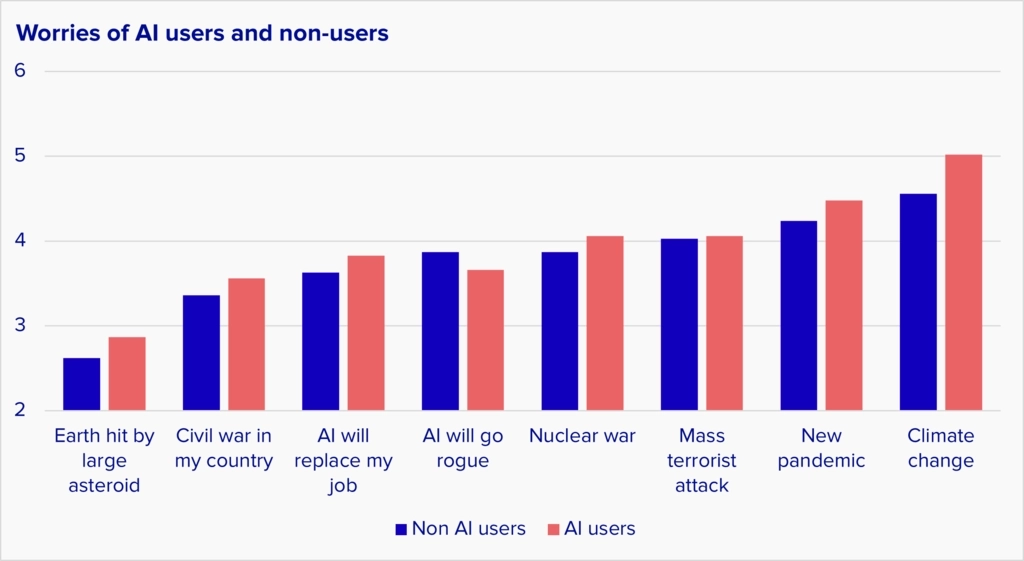

People who use AI at work are slightly less worried about it going rogue

People who use AI chatbots for work are slightly more concerned about every issue—except AI going rogue and becoming hostile to humanity. People who use AI chatbots for work are a bit less frightened of rogue AI than people who don’t use AI for work.

“Looking ahead to the next ten years, how concerned are you about the following possibilities?” Average rating on a 1-7 scale, 7 = extremely worried. “AI users” = people who use AI for work.

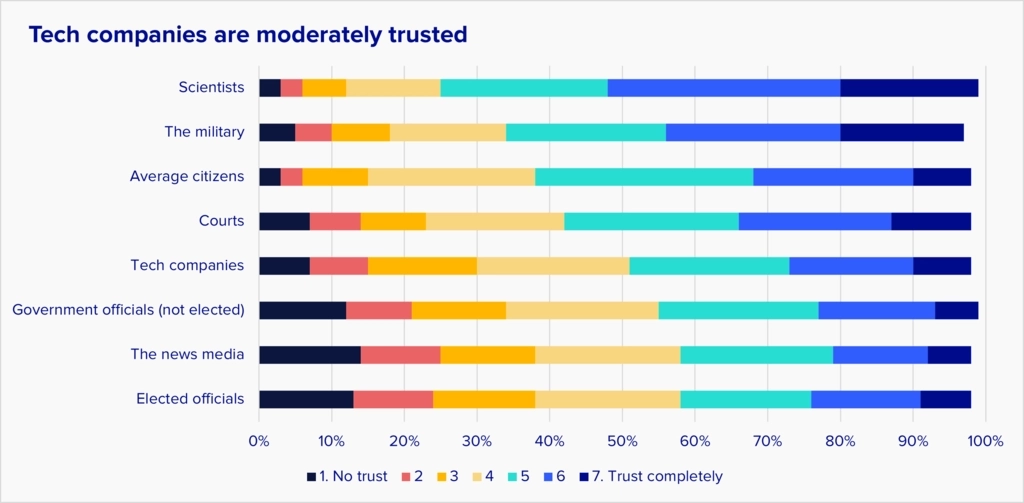

Trust in tech companies is limited

As tech companies develop world-changing products like AI, their ability to deploy them can be limited by public mistrust. To assess this issue, we asked knowledge workers how much they trust various groups and institutions to do the right thing for their country.

Tech companies were in the lower half of the rankings, slightly above government officials and the media but below every other institution on the list. Large tech companies need to find ways to earn trust because mistrust threatens their ability to operate.

“How much do you trust the following people or groups to do the right thing for your country?” 1-7 scale, 7 = trust completely. Answers are ranked by mean score. Base: All knowledge workers.

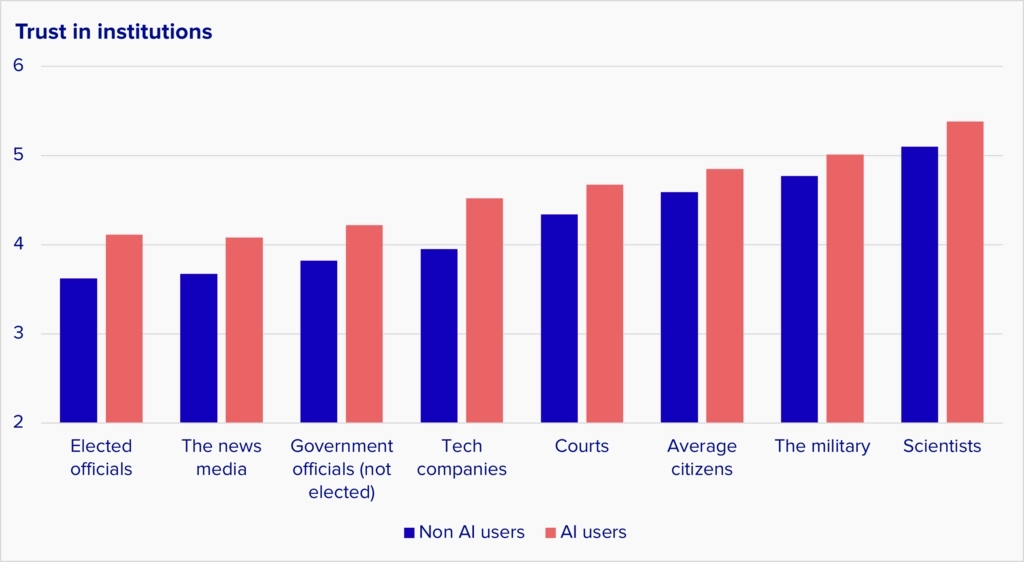

AI users are more trusting of institutions

People who use AI chatbots for work are a bit more trusting of all institutions than people who don’t use them.

“How much do you trust the following people or groups to do the right thing for your country?” 1-7 scale, 7 = trust completely. Base: Knowledge workers who do and don’t use AI in their work.

The AI chatbot triathlon

We wanted to understand how users would react to the responses from four leading AI chatbots. Did any chatbot produce more complete responses than the others? How did people feel about the responses? What did they like and dislike about them?

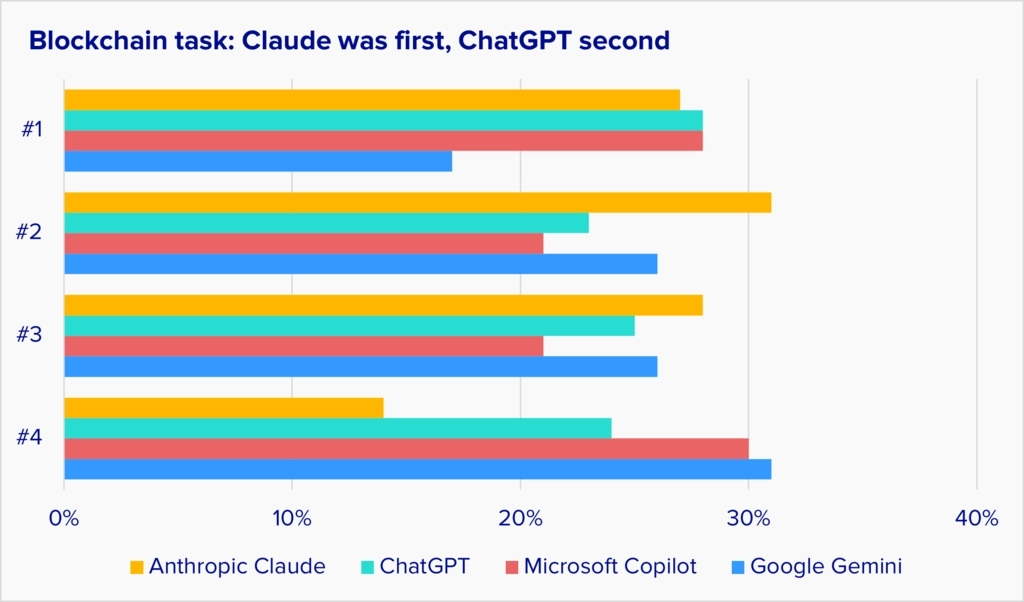

We ran 3 competitive tests where 4 chatbots—ChatGPT, Anthropic Claude, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot—were told to answer the same prompts. We copied their answers, removed any information that identified the chatbot, and showed the answers to knowledge workers. We then asked them to stack rank the responses from best to worst.

Inspired by the Olympics, we awarded medals to the winners. The bot that was rated first in an event received a gold medal, second place was silver, and third place was bronze. Here are the results.

Gold | Silver | Bronze | |

Anthropic Claude | 2 | - | - |

ChatGPT | - | 3 | - |

Microsoft Copilot | 1 | - | 2 |

Google Gemini | - | - | 1 |

Anthropic Claude won two golds, ChatGPT received three silvers, Copilot won one gold and two bronze, and Gemini won a single bronze.

Most people felt that the facts in the responses from the four chatbots were similar. The chatbots tended to cover the same information and sometimes even used the same phrases. Nevertheless, there were some significant differences between them:

- Anthropic Claude did best overall. Many people liked the way it framed its answers and appreciated how it structured information.

- ChatGPT was strong in all of the events. People cited it for having a friendly tone and organizing information well. But it was sometimes seen as stodgy.

- Microsoft Copilot polarized people. In each test it had a high number of first place votes and also a high number of last place votes. Unlike the other chatbots, Copilot mixes emojis and web links into its responses, and people tended to either really like or really dislike that approach. Some also said its answers were too long.

- Google Gemini trailed in all three events. Most people didn’t dislike Gemini, but many said its answers were too short, and criticized its word choices and phrasing.

Triathalon details

Four AI chatbots were given the same three tasks:

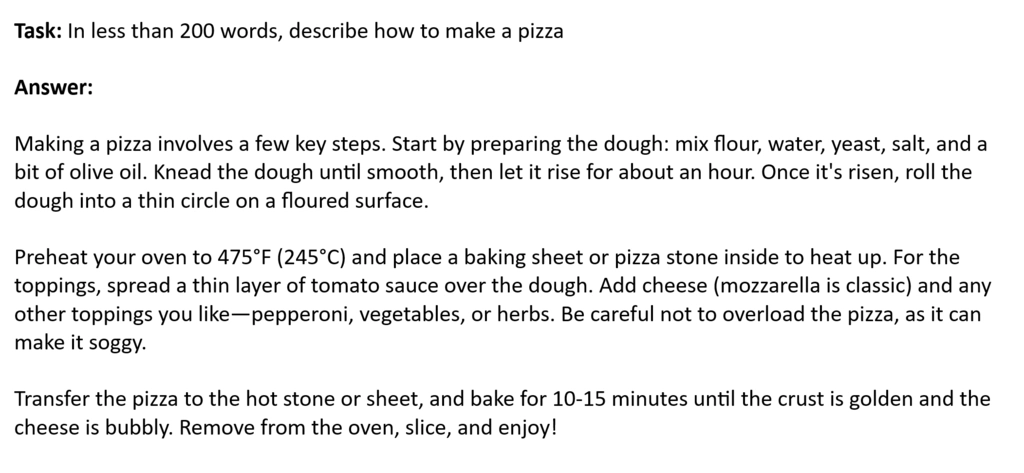

- A process challenge: “In less than 200 words, explain how to make a pizza.”

- An explanation challenge: “Using terms that the average person can understand, explain blockchain technology in less than 200 words.”

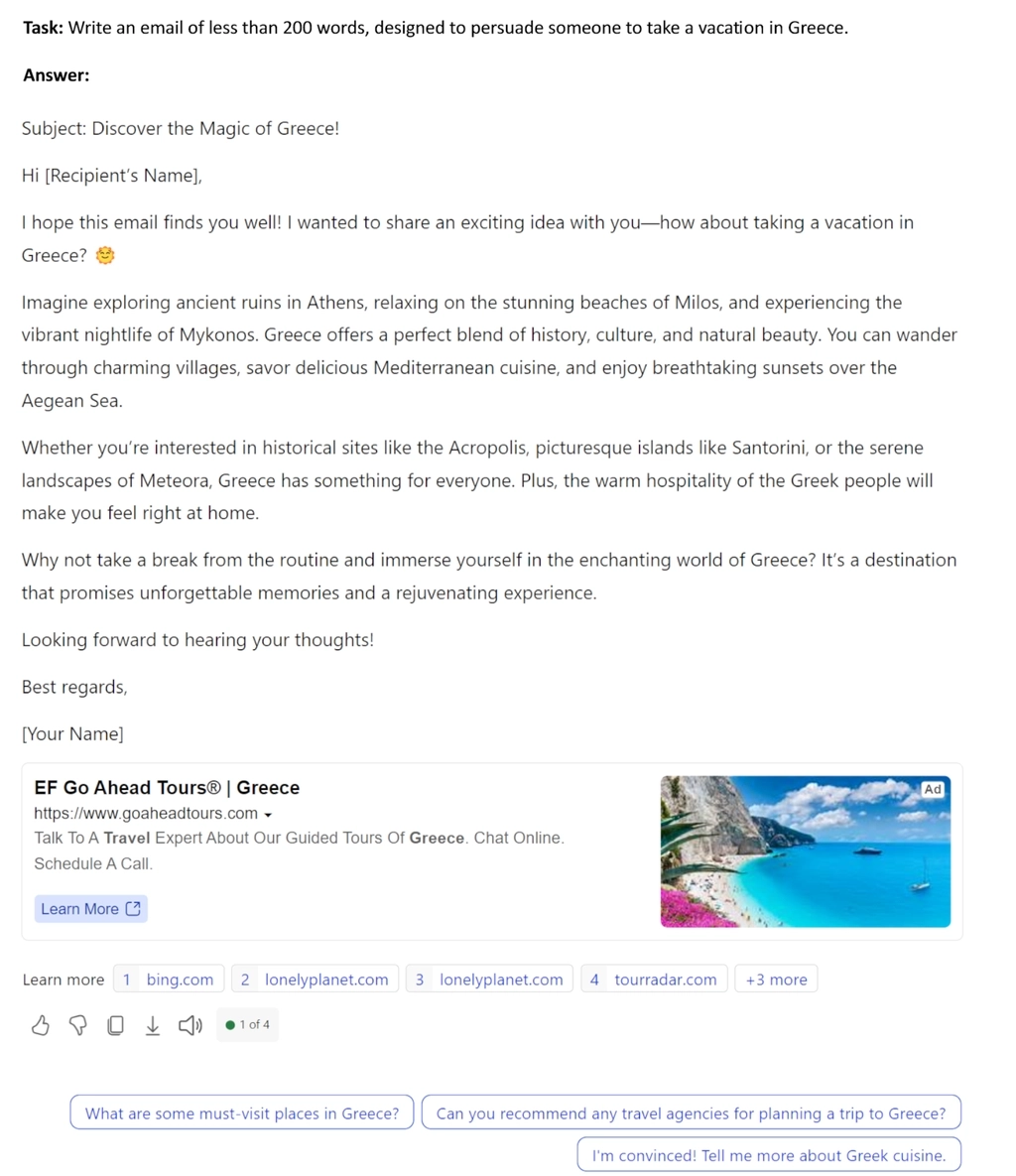

- A content creation challenge: “Write an email of less than 200 words, designed to persuade someone to take a vacation in Greece.”

We chose these tasks because they’re the types of things that many people told us they use AI chatbots for.

The chatbots’ responses were anonymized and shown to the participants, who were asked to stack rank the responses from best to worst. We also had them explain their choices.

(In case you’re wondering why we chose consumer-oriented tasks in a knowledge worker study, we found that we needed to choose topics that most people were equally familiar or unfamiliar with. If we didn’t, many people rated their understanding of the topic rather than the quality of the response. Most people understand pizza and vacation travel equally well, and most people do not understand blockchain, so that gave a level playing field.)

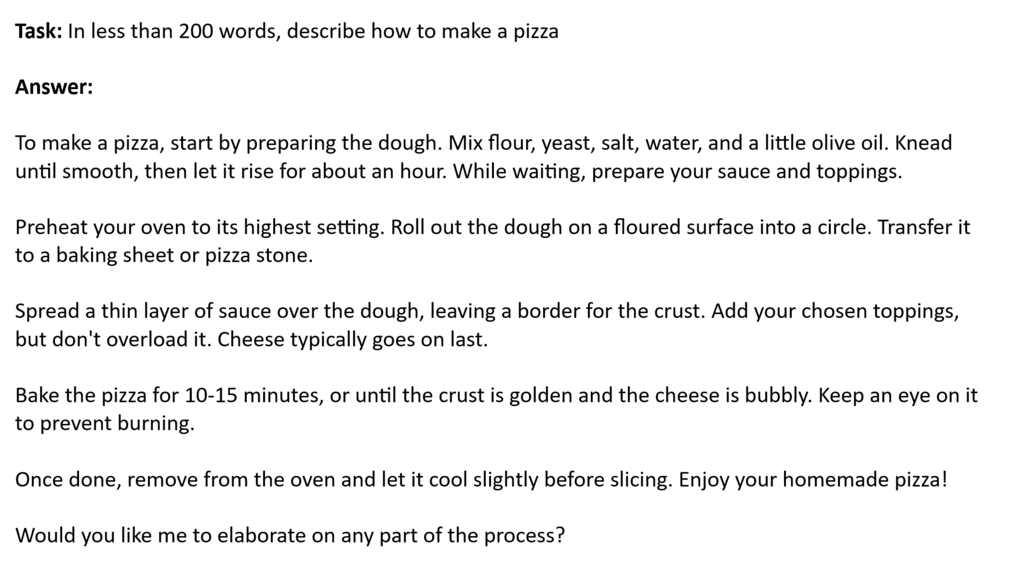

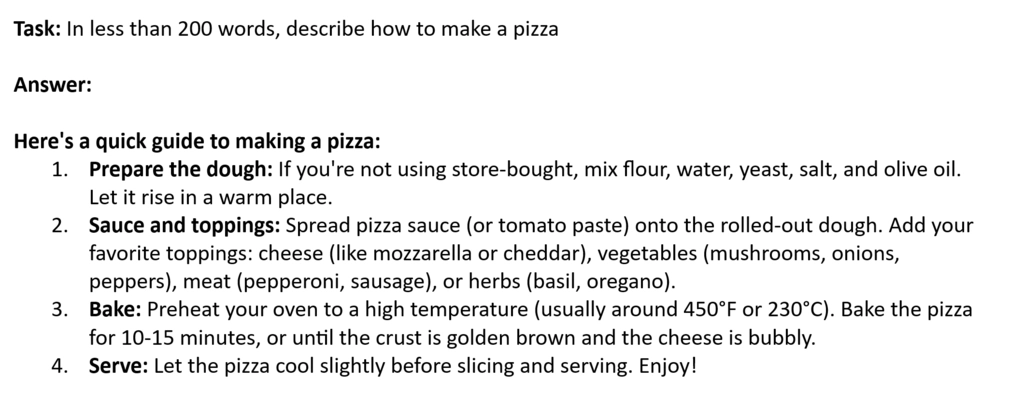

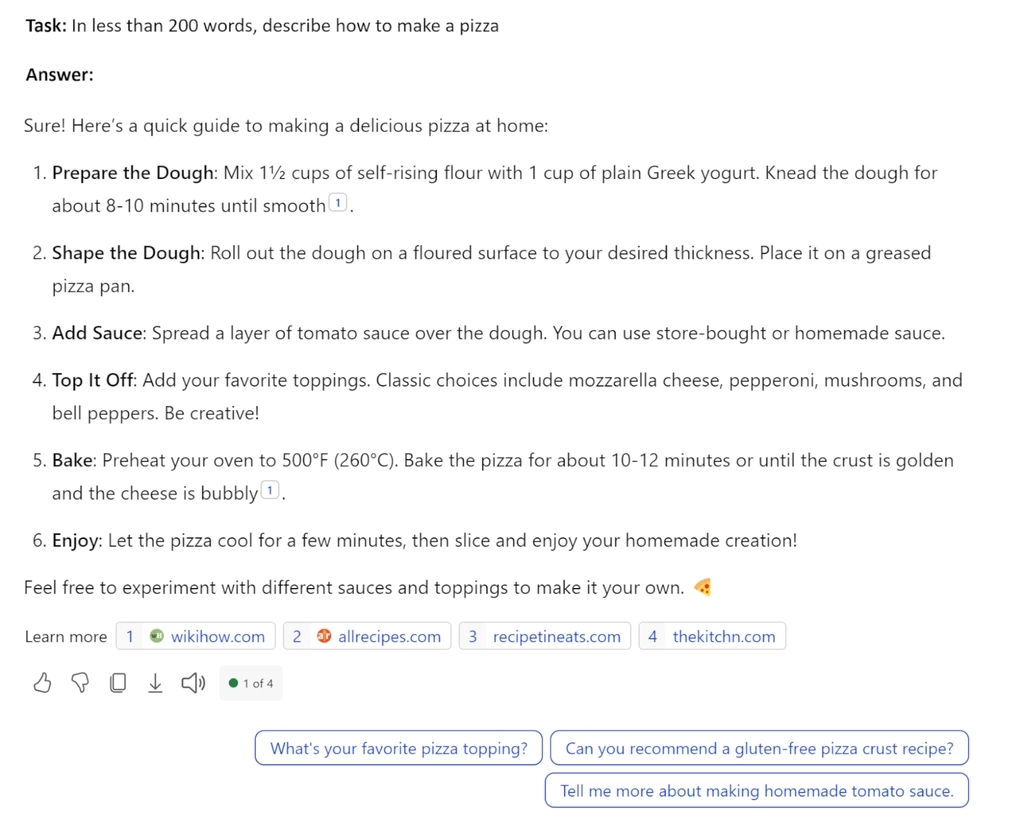

Event 1: Pizza recipe

We started with a deceptively simple task: In less than 200 words, explain how to make a pizza. The 200-word limitation forced the chatbots to compromise between describing the technique and giving specifics on the recipes. The tradeoffs tripped up some of the bots.

ChatGPT didn't give measurements for the ingredients but did discuss the technique.

Anthropic Claude didn’t give a cooking temperature or any measurements for the ingredients.

Google Gemini’s response used a numbered list but gave no measurements.

Microsoft Copilot’s response gave both a cooking temperature and measurements for the ingredients. It also included a lot of links. Some users were disturbed by the use of yogurt in the crust mix.

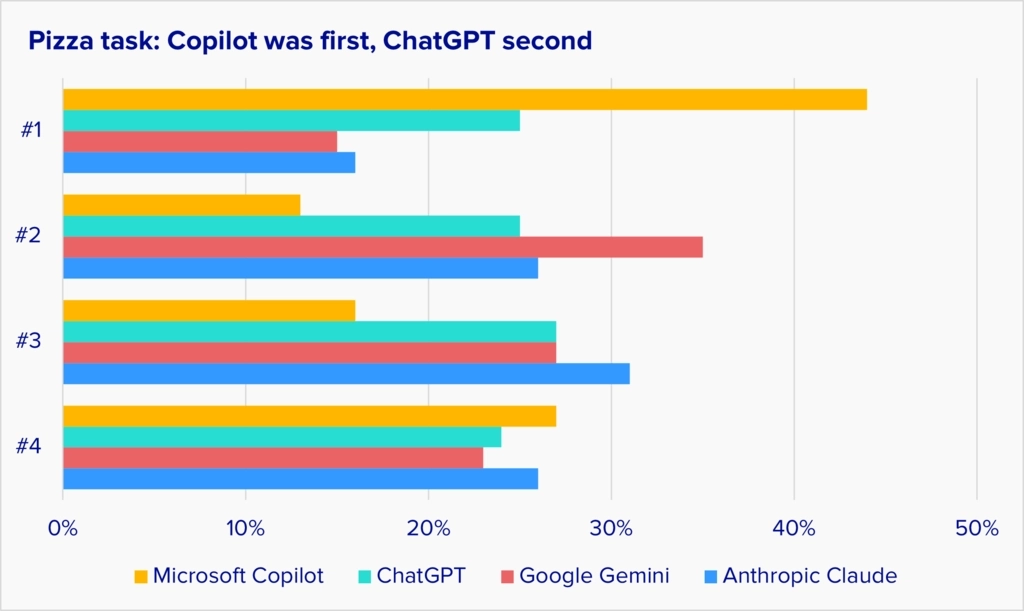

Microsoft Copilot took gold in the first event. Copilot’s more detailed response was the clear winner, but its use of yogurt and the inclusion of search links turned off some people.

Here, you can see some judges (knowledge workers) discussing the scoring:

(How we scored the event: A first-place vote from a participant counted as one point, a second-place vote was two points, and so on. The votes were totaled, and the bot with the lowest average vote was the winner. The same people judged all four platforms, and there were about 800 knowledge workers in each judging pool.)

Event 2: Explain blockchain

In this event, we gave the chatbots a challenge that would intimidate any human author: Using few words, explain an incredibly complex technical subject—in this case, blockchain technology—in terms the average adult could understand.

ChatGPT’s response didn’t have bullets or numbered points, and used vocabulary similar to most of the other chatbots:

Anthropic Claude used a numbered list, and language that was similar to ChatGPT’s:

Google Gemini focused the most on using language that the average person could understand (or maybe that a stereotypical average person would understand). Phrases like “this makes it super reliable” and “trust is super important” are distinct from the other chatbots. Gemini’s answer was also notably shorter than the others, and that cost it some votes:

Microsoft Copilot’s response had a numbered list and links. Some users liked that a lot, and others really didn’t.

Anthropic Claude took gold in the second event. Its answer was relatively detailed, and used a numbered list.

Claude’s response was first or second choice for many judges, which gave it the best average score. ChatGPT did well, but it received many more last place votes than Claude. Copilot was either loved or hated, and Gemini’s response underperformed.

Comments from the judges:

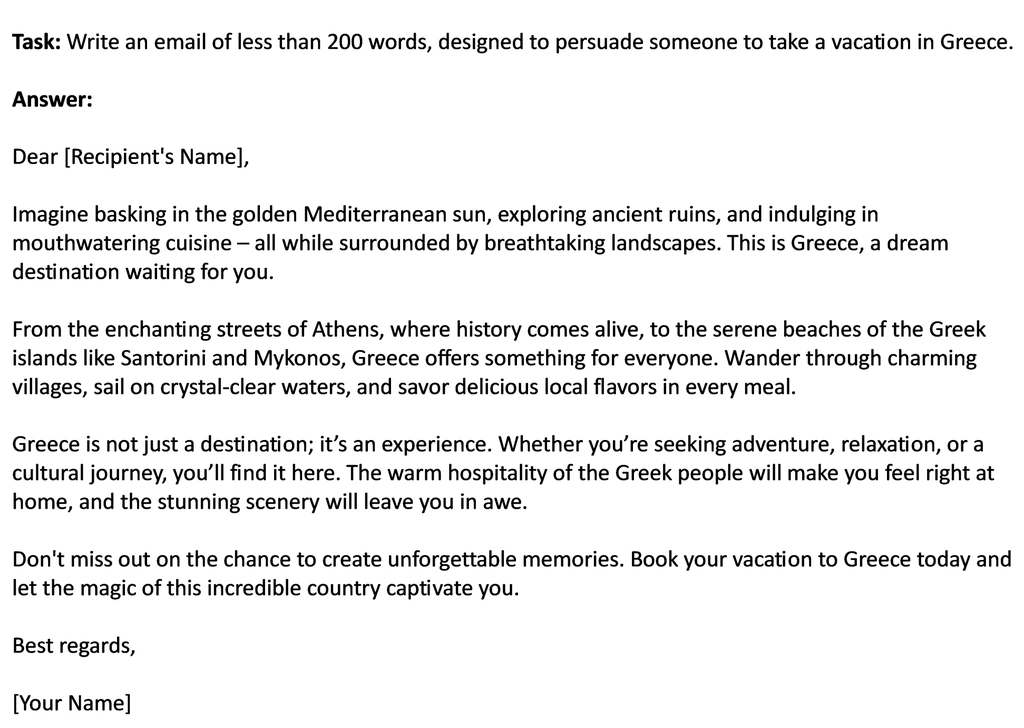

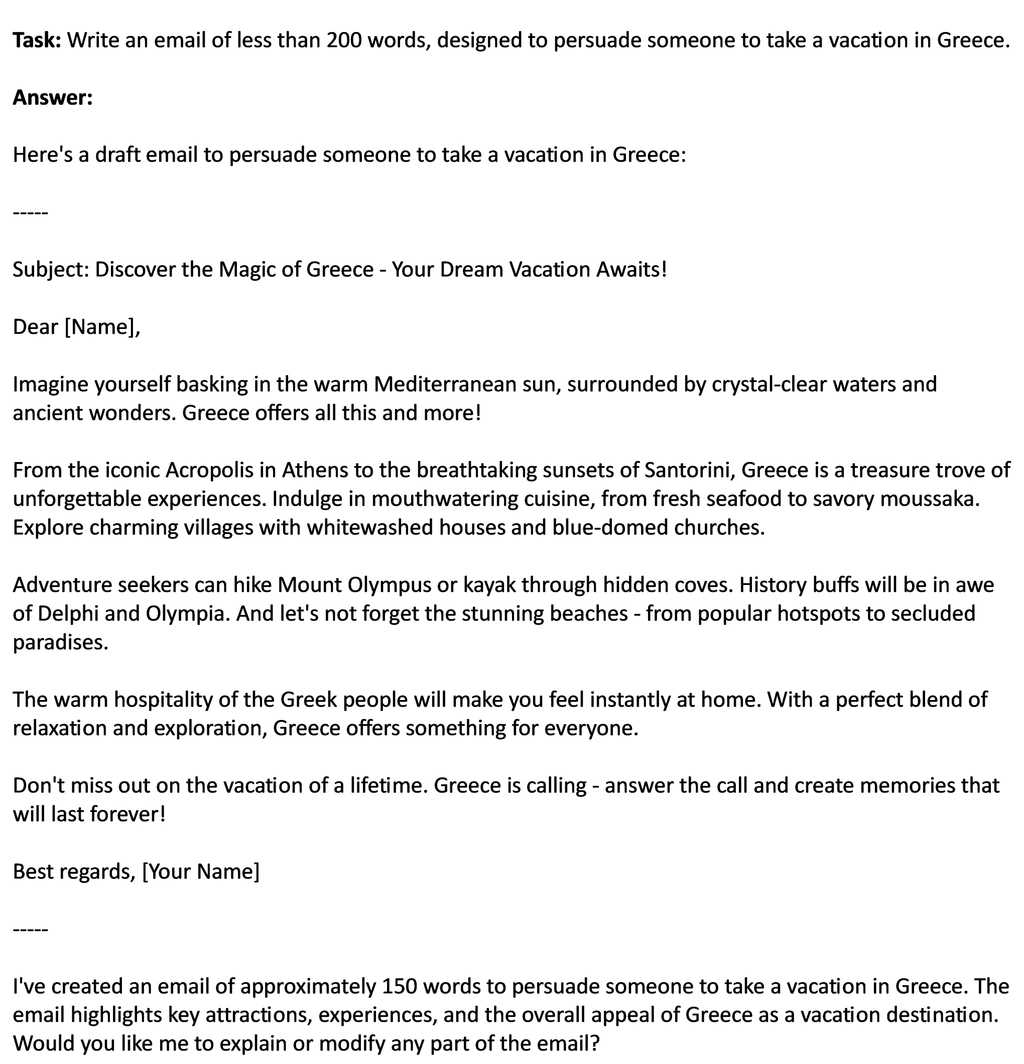

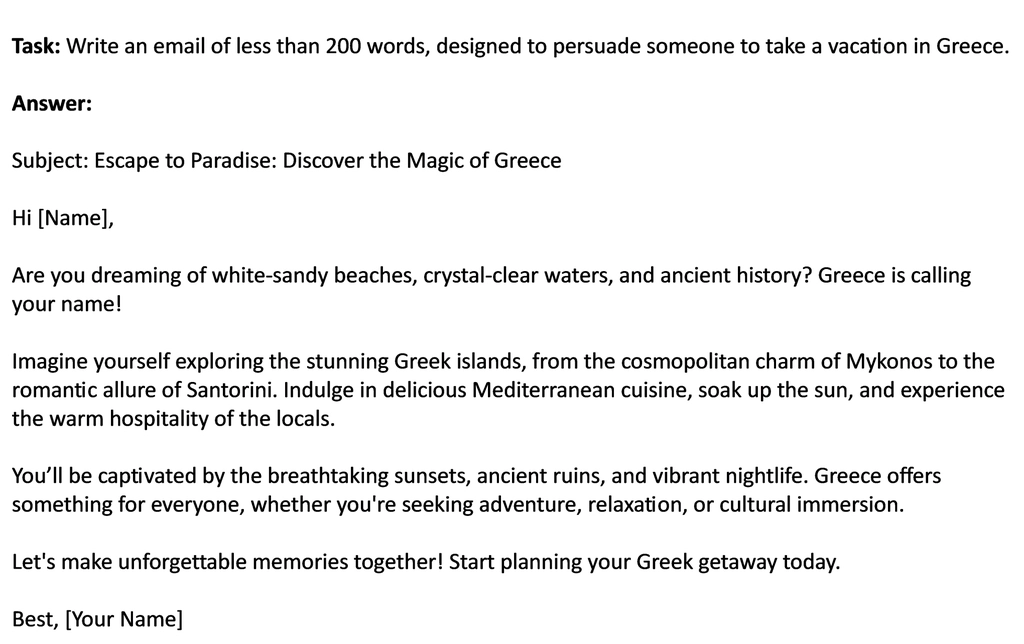

Event 3: Write an email promoting travel to Greece

In the third event, we wanted to give the chatbots a creative task, so we asked them to write a personal email encouraging someone to visit Greece. It was striking how similar the language and choice of highlights were in all four responses.

ChatGPT was the only chatbot that didn’t include a subject line for the email; some users penalized it.

Anthropic Claude gave a bit more detail, and also was the only chatbot to frame the response with an explanation.

Google Gemini’s response was shorter than the others.

Microsoft Copilot gave a numbered list and a lot of details. It also included links and an ad for a travel agency, which cost it some votes.

Anthropic Claude narrowly won the third event, followed closely by ChatGPT and Copilot. People either loved or hated Copilot’s distinctive answer. Google Gemini was a distant fourth.

Comments from the judges:

Lessons for companies from the AI chatbot triathlon

The basic information delivered by AI chatbots doesn’t vary much: the steps to making a pizza or the charms of Greece are all well known, and all the bots covered those basics well. As a result, users focused on more subtle details of tone, completeness, and organization. Attention to details drove big differences in preference:

People respond to AI conversations the same way they respond to human conversations. They make emotional judgments based on subtle differences in word choice, formatting, and overall tone. If a response was seen as too formal, users were less attracted to it. But if a response was too informal, it might be interpreted as unserious or even mocking the user. Anthropic Claude won because for most people it did the best job of balancing completeness, formatting, and approachability.

Companies creating AI chatbots and other conversational AI products need to test carefully for tone and credibility of their answers rather than just comprehension and usability.

Less is not more. People felt better about responses that had more details. You obviously don’t want to overwhelm people with information, but if they ask for a 200-word answer and you give 100 words, that’s not going to go over well. Google Gemini suffered most from this issue. Generative AI chatbots struggle to comply with word counts, so this is an area for potential differentiation if someone can get it right.

Bullets, numbers, and formatting help. When explaining a subject, answers that use bulleted and numbered lists often get better ratings than plain text. Answers that had a larger number of short paragraphs also tended to score higher than answers with a couple of long paragraphs.

Copilot shows an intriguing path forward. Microsoft Copilot was the most controversial AI chatbot: some people loved it, and others hated it. The ones who loved it appreciated the additional links it gives and the playfulness of the emojis it sprinkles in its answers. People who hated it loathed the emojis and felt that Copilot’s responses looked too much like a search engine.

All of this points to a very important choice for a company making a chatbot or other conversational AI product: How much do you differentiate your voice?

Copilot’s differentiated approach of pleasing some users and irritating others is not necessarily a bad thing. In a saturated market dominated by a big incumbent, finding a way to bite off part of the market can be a very effective business strategy. It’s often better to have some people love you (even if that makes others hate you) than to have everyone be lukewarm.

Extending that idea further, the ultimate AI chatbot might adjust its answers to each individual user’s personality, just as a human being would speak differently to a college friend at a party versus their Aunt Martha at a Sunday picnic.

It’s not clear how most users would feel about allowing an AI product to know them so thoroughly that it could make those personal adjustments. But we do think it’s safe to say that making some sort of tweaks to the tone and structure of answers is going to be an important competitive battleground in AI chatbots.

Methodology

This study focused on the use of generative AI chatbots like ChatGPT and Google Gemini. For simplicity, in the report, we refer to them as “AI chatbots” or occasionally just “AI.” However, the participants in the study understood what we were asking about.

In September and October 2024, UserTesting surveyed 2,511 knowledge workers (people who use computers in their work more than two hours a day) in five countries:

- US 997 people

- Canada 299

- UK 501

- Australia 511

- Singapore 203

In addition to surveying people, we conducted a competitive benchmark between ChatGPT, Anthropic Claude, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot. The AI chatbots were given the same tasks, and their answers were anonymized and shown to participants, who rated them on several factors and also stack-ranked them.

The survey and more than 100 follow-up video interviews were conducted through UserTesting’s platforms.

Learn more in our free on-demand webinar

Do you want to learn more about trends in AI usage and the chatbot triathlon? Do you want to educate your coworkers and management on how the AI market is changing, and what it means to employers and tech companies? Then check out our on-demand webinar on generative AI chatbots, age 2. Topics we’ll cover include:

- An overview of the study findings

- Videos of real users explaining how they use AI chatbots and how they feel about them

- A discussion of the implications for tech companies, and for every employer using AI chatbots

- The opportunity to ask questions about the study

The session will be led by Michael Mace, Executive Business Strategist at UserTesting. He works closely with enterprises to help them deploy human insight and turn it into a competitive advantage.

Mike is a 25-year veteran of the tech industry. At Apple, he was head of worldwide customer and competitive analysis, including all primary and secondary market research. At Palm, he was VP of product strategy. He also co-founded two startups, and has consulted for many companies.

How to choose and develop the right AI features

Get actionable steps to help you get your AI development right on the first try.