Six agreeable examples of GDPR ready opt-in forms

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), an EU privacy regulation designed to more rigorously protect users’ data, came into play in May 2018 and the ramifications are still being felt.

Marketing, data-collecting and online-business-owning communities frantically scrambled to bring their privacy policies in line with the new regulation. Although the hysteria may no longer be front page news, your organization still needs to be compliant – even in 2020.

Marketing insights

Discover how UserTesting helps marketers refine messaging, optimize campaigns, and drive stronger customer connections.

GDPR requires that organizations have a “lawful basis” for processing data, which can be demonstrated in a number of different ways. It’s up to them to decide which basis is the most appropriate for their situation and business model.

One such basis is consent, which in the words of the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO), “requires a positive opt-in. Consent means offering individuals real choice and control. Genuine consent should put individuals in charge, build trust and engagement, and enhance your reputation.”

As you might imagine, persuading users to actively consent to having their data used for marketing purposes is much easier said than done, and digital marketing has historically relied on methods that only have a very vague, passing relationship with the idea of consent.

Under GDPR, companies now need to at least give users the chance to consent to their details being used for marketing and other purposes, put them in charge of how those details are used and allow them the option to withdraw if they so choose.

Let’s look at six strong examples of this, from companies who’ve created great opt-in forms for obtaining their users’ consent under GDPR.

Companies with effective GDPR opt-in forms

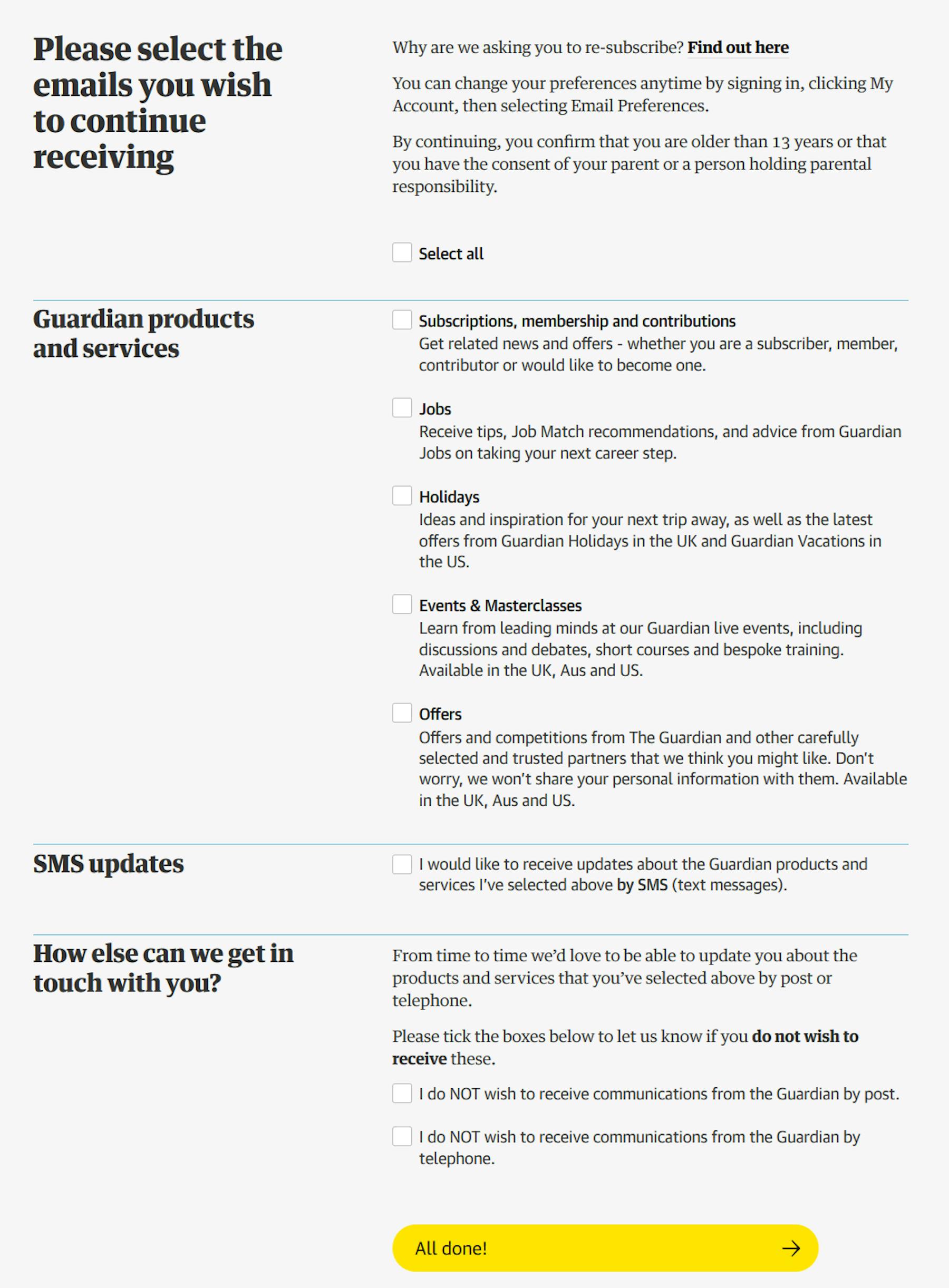

The Guardian

The Guardian is one of the first companies that we became aware was updating its regulations to comply with GDPR. The UK publisher has been proactive in reaching out to its users, via a banner while they’re logged in to the site and through emails. The banner encourages them to resubscribe to the communications they want to continue receiving.

The Guardian’s opt-in form clearly ticks a number of boxes on the positive consent front. Consent to marketing communications is separated out from consent to the site’s overall Terms and Conditions, and users are required to proactively opt in to different types of product communications they want to receive, by email and/or SMS.

The form also links to a clear explanatory page, with an informational video and an FAQ, to educate users about the context for these changes.

The Guardian’s GDPR opt-in form scores high on what’s known as “granular consent”, which as the ICO explains, requires obtaining separate consent for separate things, not “vague or blanket consent.”

It falls down, however, on the last two boxes, which require users to actively opt out of receiving communications by phone and post. As previously mentioned, consent under GDPR requires a positive opt-in from users, without using “pre-ticked boxes or any other method of default consent” (per the ICO).

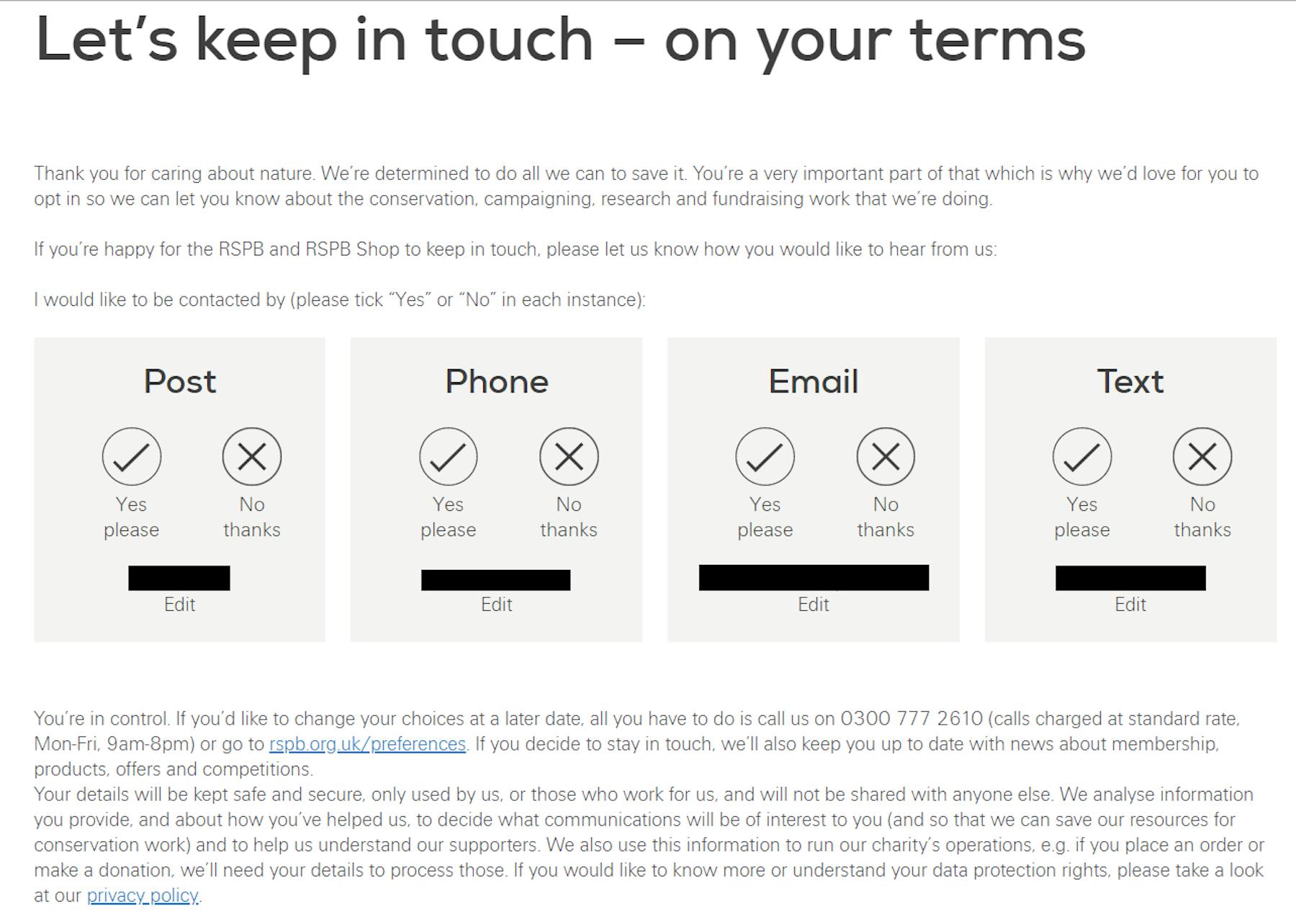

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB)

Christopher Ratcliff’s recent interview with Friends of the Earth about UX testing for GDPR highlighted how tricky GDPR can be for charities. Unlike ecommerce websites and other for-profit businesses, charities lack incentives (like discounts) that they can use to lure people into giving consent, but still have just as much need to grow their contact database.

Charities are in various states of preparation for GDPR, but one of the organizations setting a strong example is the RSPB. The charity has been reaching out to its existing supporters to encourage them to opt in to communications from the RSPB, and published a blog post in December which explained its reasons for doing so.

The RSPB’s opt-in form separates out the different modes of marketing communication, with an unambiguous tick or a cross for opting into and out of each one. At the same time, users are able to view and edit the contact details that the RSPB currently holds on them.

The RSPB also features a link to its privacy policy (albeit not prominently) and lets members know how they can update their details in future if they change their mind.

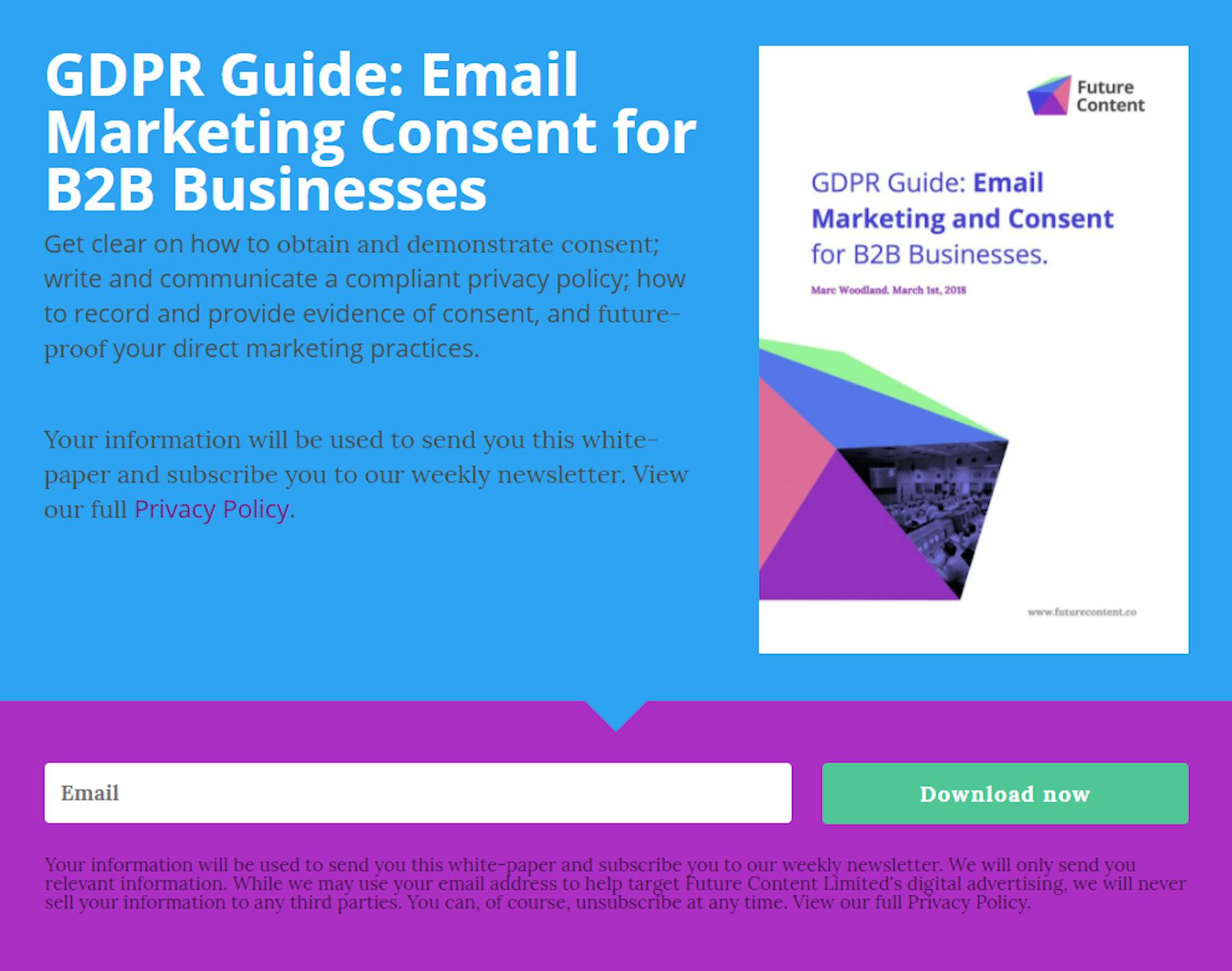

Future Content

This example from Future Content is a GDPR opt-in form in the most literal sense – a form that opts the user in to receiving a whitepaper on GDPR.

It stands to reason that the form would be GDPR compliant (or people would rightfully be skeptical of the whitepaper), but it still serves as a good example of how to make a simple sign-up form compliant with GDPR.

The form is clear and up-front about how users’ information will be used, with a prominently-featured link to Future Content’s privacy policy.

The fine print also satisfies two other important conditions of consent under GDPR, by informing users that they can unsubscribe from communications and giving details of any third parties who might access the data.

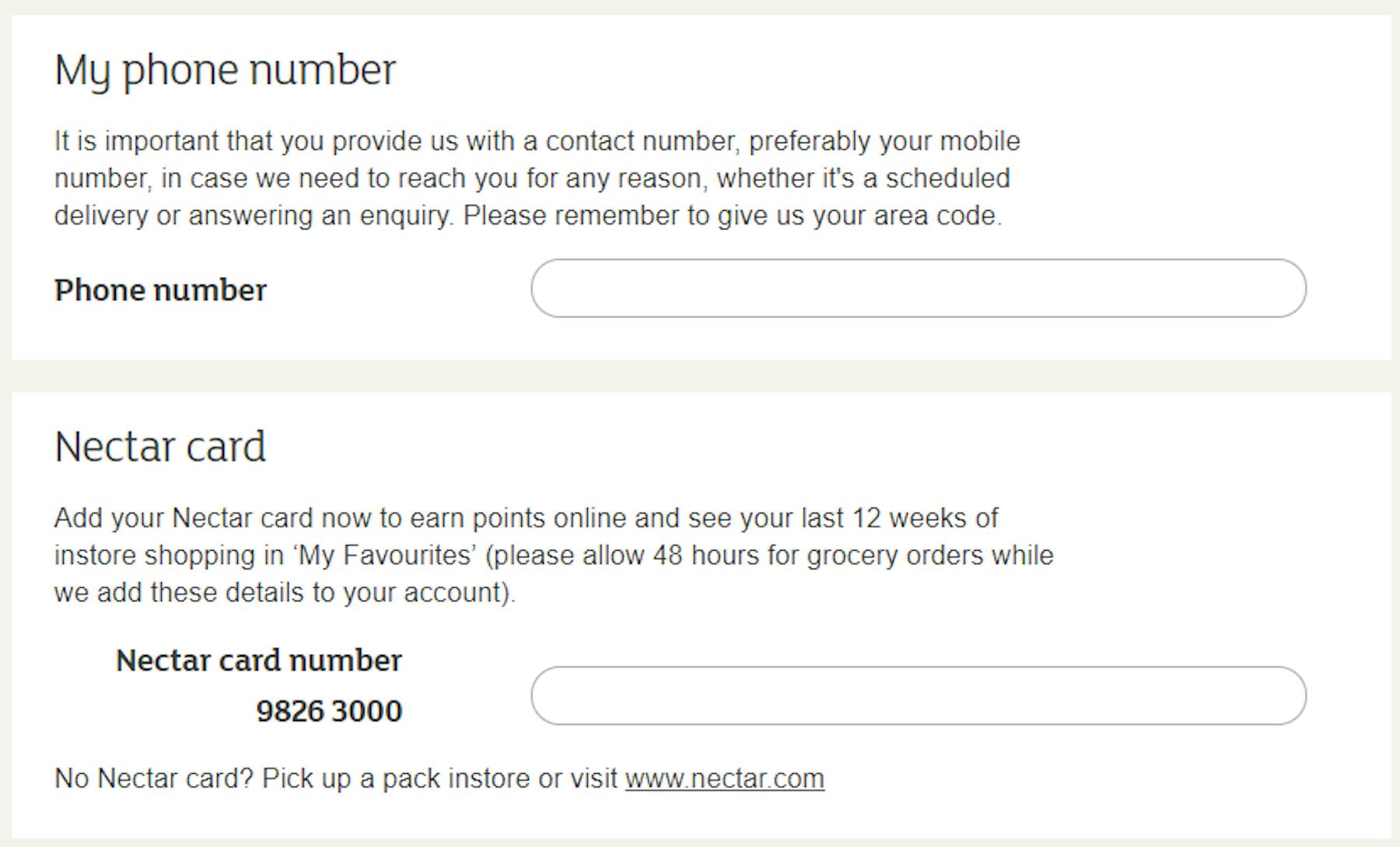

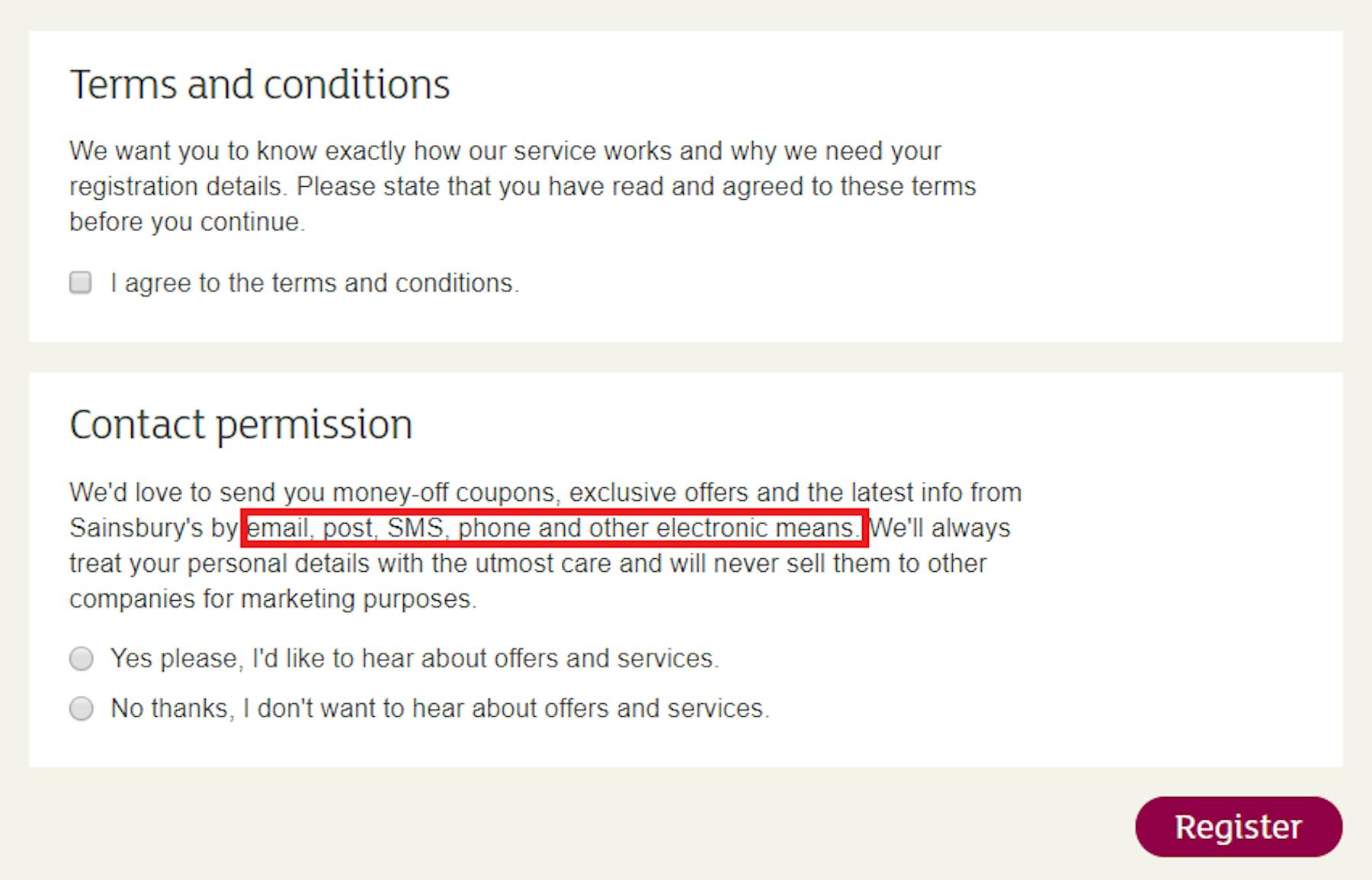

Sainsbury’s

Sainsbury’s has been featured in multiple places as a strong example of GDPR best practices.

This is well-deserved. Sainsbury’s sign-up form experience is straightforward and clear. In places where the form asks for extra personal details, such as their phone number and Nectar Card number, explanations are provided as to why the company needs them.

Sainsbury’s also clearly separates out consent to its Terms & Conditions from consent to receiving marketing communications.

These communications are strictly opt-in, with no boxes checked by default, though as Ben Davis points out in his piece, the fact that all of the different communication channels (email, post, SMS, phone and “other electronic means”) are lumped in together is less than ideal, losing Sainsbury’s some points on the granular consent front.

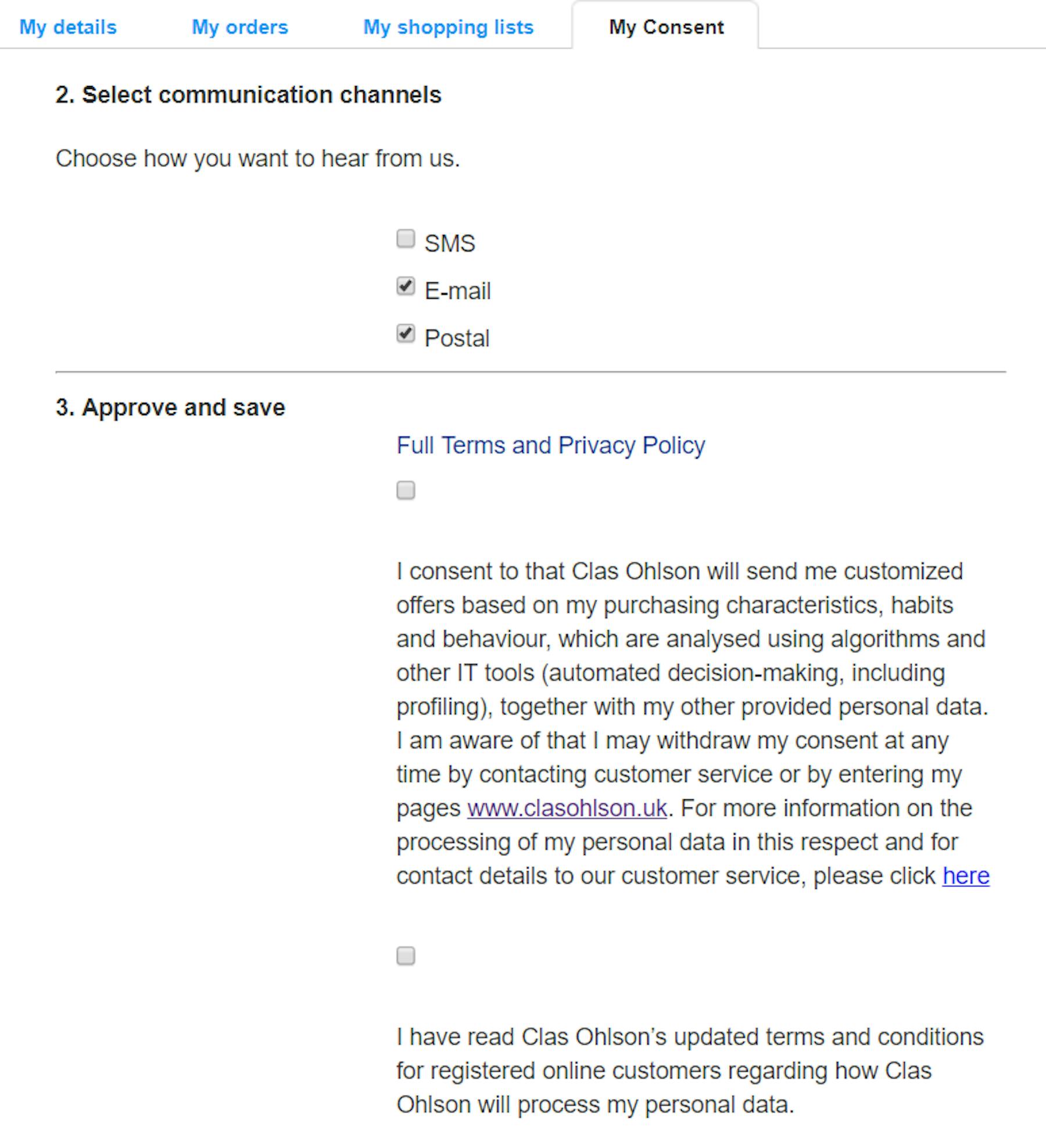

Clas Ohlson

Swedish hardware retailer Clas Ohlson is another good example of how to proactively obtain your customers’ consent under GDPR.

In addition to emailing its customers about the new regulation, the company makes its consent form easy to access at any time within users’ profile settings, under a clearly-marked ‘My Consent’ tab.

There are separate checkboxes for opting into or out of email, SMS and postal communication. However, email and postal communication are initially opted in by default. Although Clas Ohlson satisfies granular consent, they fall short for not obtaining positive consent for all channels.

Agreement to the website’s Terms of Service is clearly separated out from giving consent to receive marketing communications based on your purchasing habits, and Clas Ohlson makes sure this statement of consent is as fully-worded as possible, complete with information on how to withdraw.

However, the layout of the form is potentially misleading, with a link to the Terms of Service and Privacy Policy appearing above the marketing communications checkbox – which could lead to some users opting in to marketing communications when they meant to consent to the ToS.

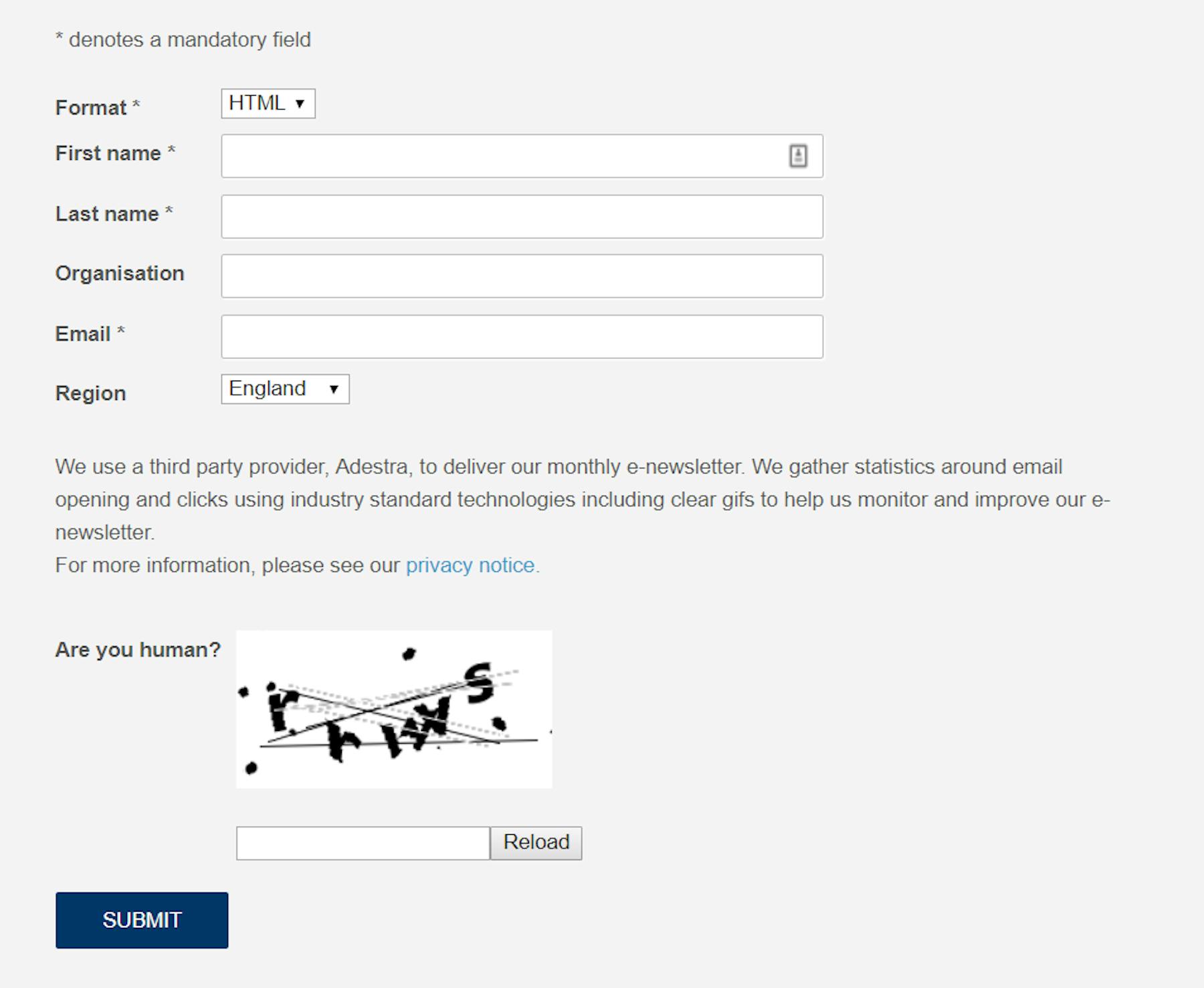

Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO)

We've quoted the ICO’s guidelines on GDPR a number of times in this article, and given the amount of guidance and best practices the ICO has published on GDPR, you would expect it to be compliant with the regulation.

However, it never hurts to check that privacy organizations are indeed practicing what they preach.

The ICO’s e-newsletter sign-up form is plain and functional, with no frills attached. Aside from the most basic information required for an electronic newsletter, the form has two additional fields, ‘Organization’ and ‘Region’, neither of which are compulsory.

Like Future Content, the ICO also explains clearly to what extent third parties are involved in handling the information, the data it collects and tracks, and why. It also links to the company’s Privacy Notice, which contains accessible explanations of GDPR and the data that the ICO collects under various circumstances.

Get actionable insights today

Uncover human insights that make an impact. Book a meeting with our Sales team today to learn more.