How to make better websites for people with dyslexia

Dyslexia is a condition that affects people’s ability to learn, read, and spell. It’s not related to intelligence – Albert Einstein, Henry Ford and F. Scott Fitzgerald are just a few notable high achievers with dyslexia.

Grahame, a user tester with dyslexia, describes his experience: “When I read, after a few minutes, the pages start to criss-cross and everything becomes distorted. Then after a few minutes of this, everything starts moving up and down. This is when I get tired, and I have to rest my eyes.”

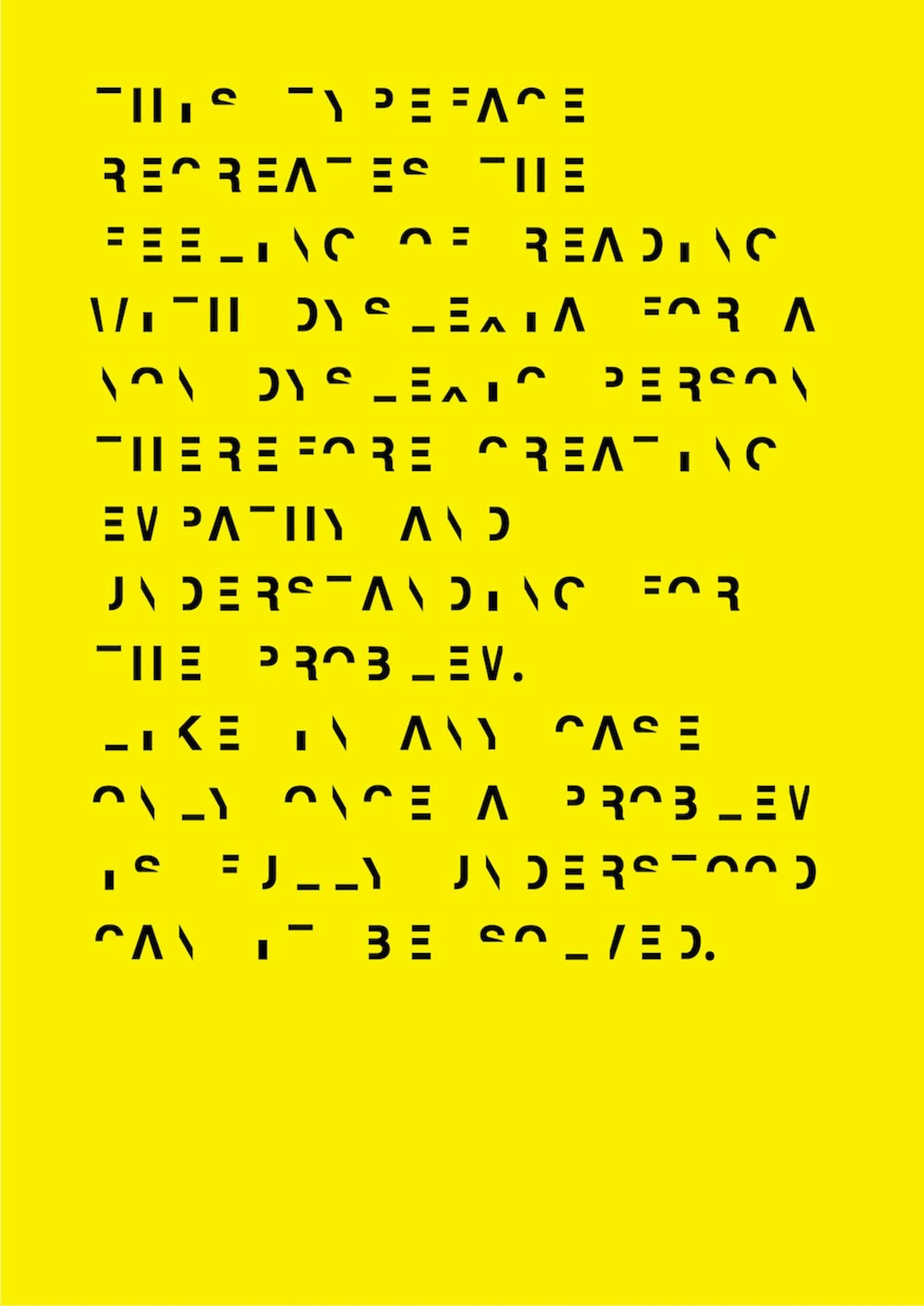

There are several ways people have tried to show what it is like to have dyslexia, such as Dan Britton’s typeface which is deliberately difficult to read.

Take a look at Victor Widell’s web page for a flavor. If you take the time to read and understand the content, you’ll realize it is slow, hard work.

People with dyslexia may also have associated conditions, such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and hand-eye coordination issues.

It’s estimated that in the UK, around 6.6 million people may have dyslexia, which is around 10% of the population. If everyone with dyslexia in the UK got together and declared independence, the Nation of Dyslexia would be the 106th biggest in the world.

Digital tools to help with dyslexia

There are quite a few aids available to help with dyslexia. The most common digital aid is text-to-speech software, which works much as you would expect – it converts text into audio. Screen reader software is also used by people with dyslexia to turn text into audio.

There are also tools to help people with creating documents, such as voice recognition software. A user can dictate what they want to write, and the software can deal with the spelling. In theory, at least.

Dyslexia is formally recognized as a disability in law. Web owners have a responsibility to make reasonable adjustments to their websites for people with dyslexia, just as they would for visually impaired website visitors.

Here are five ways to make your website better…

Five ways to make your website more inclusive

1) Structure your website properly

- Use a sans serif typeface (such as Arial) as these font types have fewer squiggles that are hard to read.

- Text size should be between 12pt and 14pt.

- Italics are best avoided, as this makes words run together. Use bold for emphasis instead.

- Use left justified text.

- Aim to have 60-70 characters per line.

Ensure the site navigation is easy to use. If your navigation relies on a search tool, the navigation structure is too complex.

Relying on a search tool as a backup, even if it checks for misspellings, is not enough. Include a site map as a safety net for people who would rather not use search.

Icons can be very useful in providing complimentary visual signposts for text navigation and section headings. A good example is the Debenhams website, that uses icons as graphical support for its text headings.

Much of that is good general practice. There are also some specific tips on making content play nicely with text-to-speech software…

Abbreviations are often read as completely different words. Text-to-speech programs usually pronounce “No.” as “No” instead of “number.” These programs often confuse acronyms and uppercase words, in line with Sod’s Law. So, acronyms are treated as words (“Usa” instead of “U.S.A.”) and vice versa (a word in uppercase for emphasis may well be spelled out letter by letter, as if it were an acronym).

Wherever possible, avoid hard-coding uppercase words into your HTML. Punctuate acronyms that shouldn’t be read out as if they were words.

2) Make your content readable

How you write is just as important as the way you present content. The Hemmingway app is your best friend in when it comes to writing dyslexia-friendly copy.

Bear these tips in mind…

- Use headings and images to help break up large blocks of text. Short paragraphs and sentences are also good practice.

- Use the active rather than the passive voice.

- Choose common words (for example, use “home” instead of “abode”).

A reader with dyslexia is more likely to recognize the shape of a familiar word. Double negatives often need a double-take from everyone, and are best avoided when writing with dyslexia in mind.

Try to summarize the main points of your writing in lists, as that is easier to digest than large blocks of text.

3) Choose your color scheme carefully

Color schemes can make a big difference for people with dyslexia. A white background can be too dazzling. An off-white, pale blue, or cream background is usually recommended, along with dark-colored text to provide good contrast.

But everyone is different, and everyone has different preferences. Given that no one size fits all – and that expensive, corporate branding guidelines often stop big changes to the visual design – providing a style sheet selector tool with several options can be a tactic to satisfy everyone.

4) Time and motion studies

It takes longer for a person with dyslexia to decode words and to understand the content, so it stands to reason that the speed they read at is generally going to be slower.

If there is content on a screen that changes automatically – such as a carousel – then you must allow enough time for someone to read it.

How much time is enough time? Again, no two people are the same, but pupils with dyslexia receive an extra 25% of time to complete exams in state schools, which is indicative of the adjustment required.

There is another problem with content that changes on the screen. The movement can disrupt the flow of a user when they are trying to complete other tasks. It hasn’t happened often, but we’ve had to abandon scenarios in user-testing sessions, because participants are so distracted they can’t carry on.

For these two reasons, we recommend that content should not change automatically on a screen. If you have a carousel, let users change the display manually, when they have had enough time to read the content.

5) Provide alternative formats

One of the great myths around accessibility is that content needs to be delivered as plain, boring text with no bells or whistles. That is an outdated idea, but especially for people with dyslexia, nothing could be further from the truth.

Given the choice, many would rather have content as audio, video, or even simple infographics rather than text. If you have the resources to deliver content in multiple formats, do so. It may help many users with dyslexia.